One of the most important events of the early twentieth century was the collapse of the Chinese Qing Dynasty during the Xinhai Revolution from 1911-12. But what was it and why did this monumental event happen? And was it inevitable? Scarlett Zhu returns to the site and explains all (PS – you can read Scarlett’s earlier article here.)

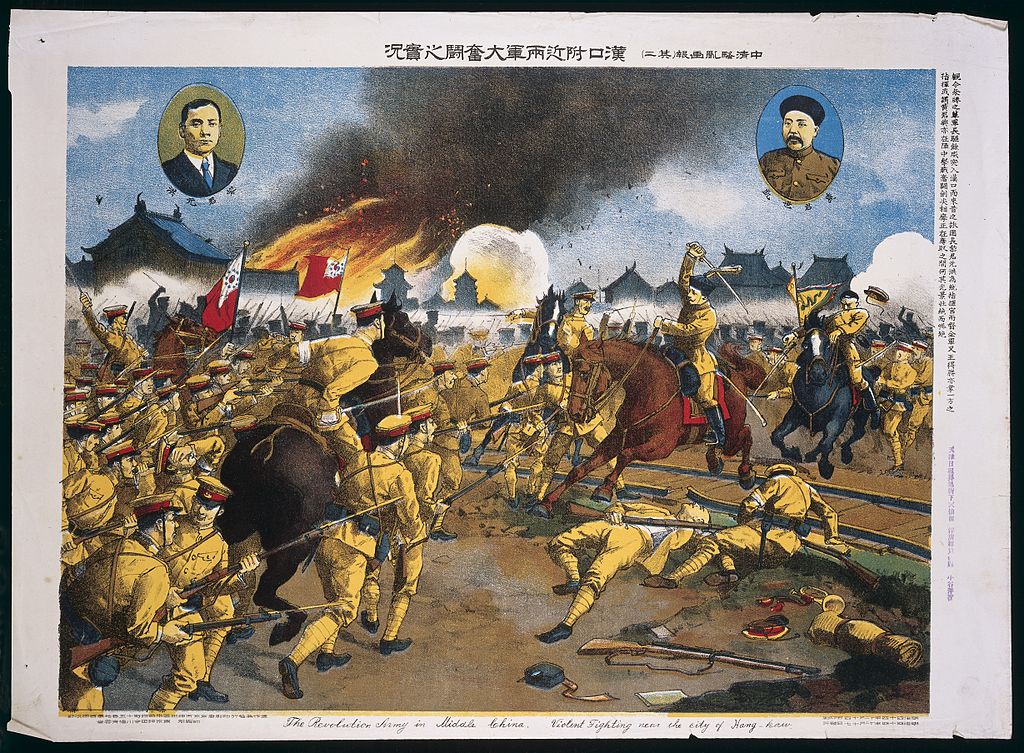

A battle outside Hankow in the 1911 Chinese Xinhai Revolution. Source: Wellcome Trust, available here.

The imperial court in the last days of the Qing Dynasty was a shadow of its former self.[1] Pressurized by the 1911 Chinese Revolution, on February 12, 1912, the Empress Dowager Longyu, with her young adopted son, the last emperor of China, Pu Yi, signed the abdication papers forcing the young emperor from the Dragon Throne. The act not only ended the Qing Dynasty at its last gasp, but also China’s millennia-long feudal rule. The reasons for the dynasty’s decline are fairly straightforward, but there has been a prolonged debate as to the relative weighting between them. It all boils down to the question of whether the nature of one event was the product of historical inevitability or a once preventable choice, whether the Qing Dynasty was destined to fall or whether it could have been saved. Some scholars argued the decisive turning point was its initial alienated identity, or Emperor Qian Long’s legacy; its internal socio-economic problems towards its final years or invasions from foreign powers. However, the more compelling case seems to be that the influence from Western societies and culture, which turned the once preventable choice into historical inevitability. Inevitability, in a historical context and in this case, would be the moment when the Qing Dynasty was incapable of avoiding the consequences of being overthrown. An assessment on inevitability and various turning points would be the best way to weigh up the importance of these factors.

An ethnic minority

It could be argued that the Qing Dynasty’s identity as a regime established by ethnic minorities determined its fate being “doomed from the beginning”. The Qing Dynasty was an empire established by the Manchus, a tribal minority which conquered Beijing in 1644. As Hsu puts it, in the end, "the very fact that the Qing was an alien dynasty continuously evoked Chinese protest in the form of secret society activities and nationalistic racial revolt and revolution."[2] The Qings did spend effort on trying to mitigate the discontent such as keeping the system of rule of the Ming government, promoting Neo Confucianism, which was a popular religion in China at the time, and allowing Han Chinese into its bureaucracy. But most of the time, it did much to show that the Manchus were separate and superior, with the prime example of prohibiting intermarriages between the Manchus and the Han Chinese. In this sense, because the majority Han Chinese would never have been content with being ruled by foreigners, internal discontent and rebellion was guaranteed. This was illustrated by the Revolt of the Three Feudatories by Han Chinese army officers in 1673. This also falls in line with Marxist historians’ view, as they see the historical process characterized by endless class struggles. In this case, it would be the oppressed Han Chinese against the oppressive Manchus, which indicated a struggle to overcome alienation successfully and thus the fall of the dynasty.

In short, the long-term resentment of the Han Chinese at being ruled by “foreigners” triggered a snowballing growth of opposition to the regime as it went on, such that it could be argued that the dynasty’s collapse became inevitable. However, this turning point was not the most decisive. This was due to the strength, assertiveness and high centralization enforced by its early founders and the fact that they all understood that the empire could only be held together by talking in political and religious idioms of their Han Chinese subjects. It meant the possibility of a submissive and marginal Han Chinese opposition and implied the survival of the dynasty was still open to them - a possibility that some argued was soon diminished when Qianlong came to power in1735.

A corrupt emperor

Emperor Qian Long’s legacy was another turning point which many argued that contributed the most to the inevitability. Despite the prosperity and peace Qian Long maintained throughout the empire, he, like many past emperors, became incompetent as a leader towards the end of his years. As the great Emperor aged, he began to adopt a series of measures which, with hindsight, planted the seeds for the inevitable downfall of the Manchus. The corruption was the most evident feature as untrustworthy officials and their needy relatives pocketed public funds. But Qianlong turned a blind eye to it, since the architect behind all this large-scale corruption and nepotism was his court favorite, He Shen. By the end of Qianlong's reign in 1796, the once-prospering treasury was “nearly depleted”[3]. In addition to this strain in the empire’s income, the untrained and ill equipped Bannerman and the Chinese Green Standard Army led by those corrupt generals was equally detrimental. This resulted in the failure to put down the famous White Lotus Rebellion in 1794 efficiently and quickly, and encouraged foreign invasions in the long term. The rebellion was significant as this was the first sign of the politicization of the general public. This was also the first peasant-led open rebellion against the extortion of tax collectors, which would eventually become a common feature towards the end of the dynasty. Furthermore, his dealings with the Europeans were also argued to encourage later aggressive foreign invasions as he adopted an isolationist approach. It could be argued that Qianlong’s reluctance to tackle corruption and to improve the quality of the military and his foreign policies made the collapse inevitable. However, the collapse at this point was not envisaged. The Qing Empire maintained goodwill from the West through trade and commerce. Alongside this, there was not a systematic breakdown within the government despite its ongoing corruption. Both factors ironically settled disputes and criticisms of the emperor, as people, whether rich or poor, high or low, were provided with great economic security, or at least from the surface it seemed this way - thus the possibility of the dynasty’s survival was still conceivable.

Weaknesses in society

The exposure of the structural socio-economic weaknesses of China in Qing’s later years, a third turning point, cannot be understated. Agriculture dominated 90 to 95 per cent of the Qing Dynasty’s rural economy[4], wealth distribution was unequal and there was significant population growth with its population exceeding 100 million, the largest hitherto in China’s history.[5] This made the economy and society incredibly weak when external shocks hit, like natural disasters and diseases. As far as Wu argued, two of the biggest floods in world history, the Yellow River flood in 1898 and the Yangtze River flood in 1911, helped to end the Qing Dynasty.[6]This pressure would ultimately tilt the balance of economic power[7] and lead to the collapse of the socio-economic system. A subsequent array of social unrest and discontent towards the Qing Dynasty was created, thus making the uneducated public more receptive to the idea of revolution. This was perhaps best illustrated by the outbreak of one of the bloodiest civil wars, the Taiping Rebellion led by the poor and the unemployed in 1850. Thus, the fact that economic and social practices, which were seen to be the backbone of the dynasty, were unsustainable meant that the fall was inevitable. However, this may not be the most convincing case. The peasants’ rebellions in response to socio-economic issues were short-lived (Dungan Revolt 1895–96) and were failures (Nian, Du Wenxiu, Dungan rebellions). Their reactions were also, to a large extent, controllable as long as Qing maintained the loyalty of the army and imposed a strong degree of force and terror. This turning point did not necessarily mean the outright fall of the Qing Dynasty, for peasants’ rebellions and the empire’s assertive suppression in response was a mode that had remained relatively unchanged for 2,000 years since the Han Dynasty[8], which ensured political stability and re-established state authority.

Foreign powers

The First Opium War in 1839 was argued to be another crucial turning point towards the inevitability of the fall, as Trotsky once described war as “a locomotive of history”[9]. It was the product of the collapse of negotiations between the British and the Chinese to open up trade barriers and soon turned China into “a drug-crazed nation”[10]. Qing’s army may have had the capacity to put down internal strikes, but they were no match for external artillery and naval strength. The event is significant in signaling the beginning of “unequal treaties” (Treaty of Nanjing, Treaty of Bogue) and a chain of foreign invasions and interference (The Invasion of the Eight-Nation Alliance). This meant that the Chinese lost confidence in the once-invincible army and the Imperial political system. In turn, this led to even more unrest in the Chinese society, with patriots enraged at the weakness of their country and forming revolutionary movements. One of the most notable was the Boxer Rebellion, which initially was against both the Qing government and the foreign spheres of influence. China’s defeats, the exacerbation of the socio-economic problems by the wars and the protests that followed did mean the empire’s future looked incredibly bleak. It seems that the collapse was highly possible. However, this turning point was not the most important one. Firstly, it is important to note that the Western powers generally had no intention to overthrow the Qing Dynasty, but rather desired to turn it into a subordinate. Secondly, the Qing government was clever enough to manipulate the patriotism in their favor. They managed to mobilize the protestors against the foreign powers, as demonstrated by the change of the peasants’ aims in the Boxer Rebellion.

Western ideas

An accomplice of foreign invasions, Western influence and culture, was argued to have a profound impact on the inevitable downfall. It reflected the great sense of crisis and highlighted the need of a change. Western modernistic literature, religion and political ideologies promised a liberal and capitalist utopia, a promotion of love and peace by Christianity and the subsequent economic prosperity following industrialization. This made the political repression of Qing seem remarkably backward and thus hugely appealed to the public. People were more educated, receptive and sensitive toward revolutionary ideas, with the example of the wave of students travelling abroad to study being radicalized, one of which became the leader in the 1911 Revolution, the “Father of Modern China”, Sun Yat-sen.

Arguably Emperor Guang Xu’s last attempt to save the country based on Western culture, the Hundred Days’ Reform in 1898, made the collapse inevitable. The example set by Western powers provided the Manchus with a route to ensure their survival. The reform consisted of numerous progressive ideas such as capitalism, constitutional monarchy, and industrialization. Despite the reform ending within 103 days, it opened up expectations which the traditional ruling elites of Qing would never be able to satisfy, particularly given their deeply rooted backward imperialism and reluctance to change. Great impetus was given to revolutionary forces within China and such sentiments directly contributed to the success of the Chinese Revolution barely a decade later, which ultimately brought down the hundred-year-old rule of the Qing Dynasty.

The key factors

Two elements indicate that the Chinese Revolution of 1911 was the decisive turning point for the destiny of the Qing Dynasty. Firstly, it was the first time that such a huge wave of universal discontent rose. It was the outburst of the accumulation of national resentment, unrest and instability. Reasons for the outburst varied, ranging from the failure of Qing to reduce the ethnic alienation, to confront foreign aggression, to solve socio-economic problems, which united a vast number of people with a variety of class, background and interests. Started by the mishandling of the building of a railway, the situation soon escalated into successive and spontaneous uprisings that occurred throughout the year across remarkably different regions. By the end of the year, 14 provinces had declared themselves against the Qing leadership.[11] Debatably the previous rebellions had been motivated by the same factors, but never had the public been so aware of the sharp contrast between the East’s backwardness and the West’s superiority, which brings in the second factor. It was the immense exposure to Western cultural influence and ideologies which heightened the pressure on the regime. China’s issues across all aspects of society were evident and the possibility of their nation pursuing the path of the modern powerhouses like Britain and France seemed achievable. This in turn also gave the leadership the ideas it needed, as it was mainly led by groups of intelligentsia who received profound influence from Western education, such as Sun Yat-sen. Hence when universal discontent met foreign ideologies, the collapse of the imperial Qing Dynasty had finally become inevitable.

The end

Thus before the Chinese Revolution of 1911, the dynasty’s collapse has always been a preventable choice. Sun Yat-sen once said that when he first advanced the Principle of Nationalism, he won responses mostly from secret societies but "seldom from the middle-and-above social strata"[12]. This is highly suggestive of the fact that the essential elements and support for the collapse was absent previously. It also indicates the impromptu nature of the 1911 revolution. However, as progressive Western ideas prevailed and nationalism spread at a tremendous pace, penetrating into every stratum of society, almost everyone came to realize the necessity of waging a revolution.[13] By claiming the fall was made inevitable by Qing’s initial identity or Qianlong’s legacy would be a claim largely reliant on hindsight. Its internal socio-economic issues, on the other hand, were persistent and prolonged by the use of fear and terror. The West’s invasions by warfare can be regarded to be far less important than the invasions by culture and ideologies, as foreign powers only envisioned the Qing to be a submissive puppet government. In conclusion, until the Qing Dynasty was highly exposed to the Western ideologies which nurtured a high level of awareness for change and comparison, its downfall was never inevitable.

Did you find this article interesting? If so, tell the world. Tweet about it, like it, or share it by clicking on one of the buttons below.

You can read Scarlett’s article on the burning of the Summer Palace by the British and French here.

[1] The Extraordinary Life of The Last Emperor of China, Jia Yinghua, 2012

[2] The Myth of the 'Five Human Relations' of Confucius, Hsu Dau-lin, 1970-71

[3] http://www.newworldencyclopedia.org/entry/Qianlong_Emperor

[4] A Changing China: Emerging Governance, Economic and Social Trends, Civil Service College, P71

[5] China’s Population Expansion and Its Causes during the Qing Period, 1644–1911, Kent Deng, P6

[6] History of the Qing Dynasty, Annie Wu, 2015

[7] Manslaughter, Markets and Moral Economy, Thomas M. Buoye

[8] A Changing China: Emerging Governance, Economic and Social Trends, Civil Service College, P71

[9] Report on the Communist International, Leon Trotsky, 1922

[10] Pathway to the Stars, DD Rev Ernest a. Steadman, 2007

[11] http://www.britannica.com/event/Chinese-Revolution-1911-1912

[12] Sheng Hu, "Anti-imperialism, democracy and industrialization in the 1911 Revolution," in The 1911 Revolution: A Retrospective After 70 years, 9-25. Beijing: New World Press, 1983.

[13] Shu Li, "A Re-Assessment of Some Questions Concerning the 1911 Revolution." in The 1911 Revolution: A Retrospective After 70 years, 67-127. Beijing: New World Press, 1983.