As allies, Japan and Nazi Germany collaborated together at times during World War 2. One such time was with the Yanagi missions, a series of fascinating submarine voyages undertaken by Imperial Japan to exchange technology, valuable materials and skills with Nazi Germany. These missions make us think – what might have been accomplished had this seemingly hollow ‘marriage of convenience’ placed greater strategic emphasis on collaboration?

Felix Debieux considers this question.

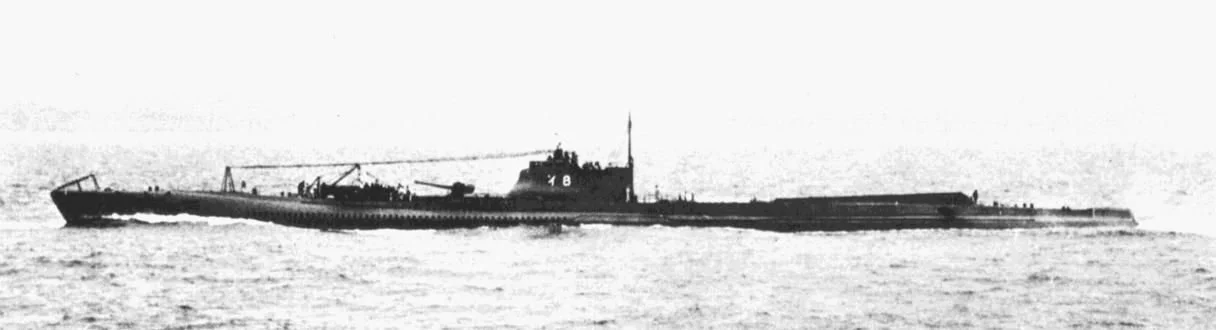

The Japanese I-8 submarine in 1939. It was to take part in the Yanagi missions in 1943.

What if – an alliance of missed opportunity?

When we talk about history, it is hard not to think about the what-ifs, the what-might-have-beens and the what-could-have-beens. Such counterfactual thinking can be traced back to the very beginning of Western historiography, when Thucydides and Livy wondered how differently their own societies might have turned out, “if the Persians had defeated the Greeks or if Alexander the Great had waged war against Rome”. More recently, an anthology published in 1931 included an essay by Winston Churchill titled, ‘If Lee Had Not Won the Battle of Gettysburg’. It imagined an alternative outcome to the American Civil War in which the Confederacy triumphed over the Union. Having read history to a postgraduate level, my impression of the counterfactual approach was pretty much the same as most professional historians. At best it was a harmless bit of fun, at worst it was dodgy, unacademic terrain completely unworthy of serious scholarship. In the somewhat less diplomatic words of Marxist Historian E. P. Thompson: “Geschichtswissenschlopff, unhistorical shit”.

Shit it may be, but that has not halted the imagination of authors who have spawned an entire genre of speculative fiction. One example which succeeded in grabbing my attention is Philip K. Dick’s The Man in the High Castle, an alternate history in which Nazi Germany and Imperial Japan overcame the Allies to win the Second World War. Having at last finished watching Amazon’s onscreen adaptation of the story, I was left wondering how the alliance between the two Axis powers functioned in reality. Was it always the antagonistic and frosty partnership portrayed in The Man in the High Castle? You may be surprised to learn, as I was, that despite the vast geographical distances, there are in fact examples of cooperation between the two powers which do not feature prominently in our conventional retelling of the war. One such case is the Yanagi missions, a series of fascinating submarine voyages undertaken by Imperial Japan to exchange technology, valuable materials and skills with Nazi Germany. These missions make us think – what might have been accomplished had this seemingly hollow ‘marriage of convenience’ placed greater strategic emphasis on collaboration? Let’s start by taking a look at the early days of the missions.

Early strategic compatibility

Following Japan’s surprise offensive on Pearl Harbour and Germany’s declaration of war on the United States, the Axis Tripartite Agreement of September 1940 was amended to provide for an exchange of strategic materials and manufactured goods between Germany, Italy and Japan. At the outset, these voyages were made by surface ships and were dubbed Yanagi (Willow) missions by Japan. As the Axis began to lose its foothold in the naval war, submarines naturally came to be seen as a safer transport option.

As early as March 1942, German naval high command – hoping to alleviate pressure on its Kriegsmarine – requested that the Imperial Japanese Navy (IJN) launch offensive operations against Allied ships in the Indian Ocean. In April that year, the Japanese agreed to send forces to the east coast of Africa to reinforce their German allies. Shortly afterward, the IJN’s 8th Submarine Squadron was withdrawn from its mission in the Marshall Islands and dispatched to Penang, Malaya.

Commander Shinobu Endo’s I-30 was among the first submarines assigned to the 8th Squadron. On 22nd April, I-30 departed Penang and just a week later assisted in the detachment’s successful attack on British shipping in Diego Suarez, Madagascar. In addition to losing a tanker, the British HMS Ramillies was heavily damaged. Following the skirmish, I-30 set off from Madagascar and was ordered on the very first submarine Yanagi mission.

The first submarine Yanagi mission

On 2nd August, four months after it had departed Penang, Endo’s I-30 entered the Bay of Biscay. Off the coast of Cape Ortegal, Spain, he was met by eight Luftwaffe bombers that provided air cover. Three days later, he was joined by a flotilla of minesweepers and escorted to Lorient — then the largest of five German U-boat bases on the French coast.

This was a historic achievement. Indeed, I-30 was the very first Japanese submarine to arrive in Europe. To mark the occasion, Grand Admiral Erich Raeder, head of the Kriegsmarine; Admiral Karl Dönitz, commander of the U-boat force; and Captain Tadao Yokoi, Japanese naval attaché to Berlin, waited to greet Endo and the crew of I-30. Music greeted them at the Lorient station and Endo was presented with a bouquet of flowers. Meanwhile, the Japanese cargo was unloaded:

3,300 pounds of mica.

1,452 pounds of shellac.

Engineering drawings of the Japanese Type 91 aerial torpedo.

The Germans were also keen to offer the Japanese their technological expertise. For example, the Kriegsmarine examined I-30 and concluded that its noise levels were unreasonably high - high enough to be detected by enemy ships or aircraft. The Germans generously fitted I-30 with some improvements, notably a Metox Biscay Cross passive radar detector and new anti-aircraft guns. Footage was also shot during I-30’s floatplane test flights, and stories were released detailing a Japanese naval air corps operating from French bases.

While all of this was going on, Endo travelled to Berlin where Hitler presented him with the Iron Cross. The visit came to an end on 22nd August, when I-30 slipped out of the sub pen and began its journey home. Its cargo included a complete Würzburg air defence ground radar with blueprints and examples of German torpedoes, bombs and fire control systems. Most valuable of all to the mission, the submarine also carried industrial diamonds valued at one million yen and fifty top-secret Enigma coding machines.

A month later, I-30 rounded the Cape of Good Hope and entered the Indian Ocean. Early on the morning of 8th October, the sub arrived back at Penang. Rear Admiral Zenshiro Hoshina, chief of the IJN’s logistics section, waited patiently to receive ten of Endo’s Enigmas. Two days later, I-30 slipped its moorings yet again and headed south for Singapore.

The following morning, I-30 made its way into the port. Indicative of the importance of the mission was the presence of Vice Admiral Denshichi Okawachi of the First Southern Expeditionary Fleet, who was on hand to greet Endo and his senior officers. Understandably desperate to return home after thousands of miles of submarine travel, that very afternoon Endo set sail for Japan. It was perhaps the height of bad luck when, just an agonising three miles from its final destination, that I-30 struck a mine. While the submarine was lost, miraculously Endo and the majority of his crew were rescued. Divers were immediately dispatched to recover I-30‘s cargo, but they found that the Würzburg radar had been destroyed in the explosion and its technical drawings rendered useless by saltwater. In addition, the remaining Enigma machines were lost, an embarrassment that was hidden from the Germans for four months.

Despite the somewhat ignominious conclusion of the mission, officials on both sides of the alliance were clearly excited by what had been learned and the potential of future exchanges. But with so many surface ships sunk by the Allies, how could the mission be scaled up? The Germans had the answer. On 31st March 1943, the Japanese ambassador to Germany, Hiroshi Oshima, cabled Tokyo a recommendation from their allies that large, older U-boats should be converted to carry war materials between Europe and the Far East. Unfortunately for Japan, Oshima’s cable was decoded by the Allies.

The missions continue

On 1st June 1943, I-8 departed Kure, Japan, with I-10 and submarine tender Hie Maru. Commander Shinji Uchino had just been given his orders to proceed to Lorient. Their cargo:

Two Type 95 oxygen-propelled torpedoes.

Technical drawings of an automatic trim system.

A new naval reconnaissance plane.

Nine days later, the mission arrived in Singapore and added to their cargo quinine, tin and raw rubber. On 21st July, nearly two months after departing Japan, I-8 crossed into the Atlantic. The only greeting to welcome the crew this time were terrible storms that pounded the submarine for ten days.

Eventually, the by now very weary Japanese crew received their first contact from the Germans. A sign of the Axis’s changing naval fortunes, a German radio signal alerted I-8 to air patrols searching from the skies above. These patrols forced a change of plan, and - after waiting for five days - I-8 received a second message from their allies: forget Lorient, make for Brest.

Once they crossed the equator, it was not until 20th August that the Japanese rendezvoused with Captain Albrecht Achilles and his U-161 submarine. The next day, I-8 took aboard a German Lieutenant and two radiomen. As with the previous submarine mission, the Germans were keen to make improvements and wasted no time installing a more sophisticated radar detector on I-8’s bridge. Eleven days later, the Japanese finally arrived at Brest – a whole three months after their initial departure from Kure. A German news agency announced that even the Japanese were now operating in the Atlantic!

More bountiful than I-8’s outbound shipment was the cargo it departed from Brest with on 5th October 1943. Indeed, the submarine set sail with:

Machine guns.

Bombsights.

A Daimler-Benz torpedo boat engine.

Naval chronometers.

Radars.

Sonar equipment.

Electric torpedoes.

Penicillin.

This time, the Yanagi mission included not just technological but also human resources. Welcomed aboard I-8 were Rear Admiral Yokoi and Captain Sukeyoshi Hosoya, naval attaché to Berlin and to France respectively. Also aboard were three German naval officers, an army officer and four radar and hydrophone technicians. We can only wonder how the dynamics of the Japanese crew were affected by the arrival of their German comrades.

It did not take too long for I-8 to run into trouble. After crossing back over the equator, a position report was transmitted to the Germans but – unfortunately for the mission – the report was intercepted by the Allies. The very next day I-8 was targeted by antisubmarine aircraft, but it succeeded in pulling off a crash-dive escape.

By 13th November 1943, I-8 passed Cape Town. That same day, I-34 – which was travelling to France on a Yanagi mission of its own – earned the unfortunate distinction of being the first IJN submarine sunk by the British. This served as a powerful reminder of the danger posed to the Yanagi missions, and so I-8 was ordered to head straight for Singapore where it arrived on 5th December.

At Singapore, I-8 anchored near to Commander Takakazu Kinashi’s I-29. I-29 had just arrived from Japan and was about to embark on its own long journey. During an encounter between the two submarine commanders, Uchino warned Kinashi of the Allied air patrols and praised the German Metox radar detector that he had received from U-161 back in August. The technological benefits of the Yanagi missions had already started to prove themselves. On 21st December 1943, I-8 arrived back in Japan having finally completed its 30,000 mile, seven-month long journey. Uchino travelled to Tokyo and presented his report to Admiral Osami Nagano, chief of the naval general staff, and navy minister Admiral Shigetaro Shimada.

Experienced hands

Although Commander Takakazu Kinashi was a distinguished submarine captain, he had not yet had the opportunity to participate in any previous Yanagi missions. Earlier in the war he had become Japan’s submarine hero, credited with the sinking of U.S. Navy carrier Wasp in September 1942, and with damaging the battleship North Carolina and the destroyer O’Brien, which eventually sank. His assignment to the Yanagi missions again underscores their strategic importance (at least to the Japanese).

On 5th April 1943, I-29 left Penang carrying an eleven-ton cargo. This consisted of:

One Type 89 torpedo.

Two Type 2 aerial torpedoes.

Two tons of gold bars for the Japanese embassy in Berlin.

Schematics of a Type A midget submarine and of carrier Akagi, which the Germans wanted to study as they constructed their own carrier Graf Zeppelin.

Twenty days later, I-29 arrived at a predesignated point 450 miles off the coast of Madagascar where it met Captain Werner Musenberg and U-180. The German sub had left Kiel on 9th February carrying blueprints for a Type IXC/40 U-boat, a sample of a German hollow charge, a quinine sample for future Japanese shipments, gun barrels and ammunition, three cases of sonar decoys, and documents and mail for the German embassy in Tokyo. Of strategic significance to the war in Asia, the U-boat also carried an important passenger: former Oxford University student Subhas Chandra Bose, the head of the anti-British Indian National Army of Liberation. The two submarines met on 26th April.

The next day, Bose and his group transferred from U-180 to I-29 and two Japanese officers switched in the other direction. The eleven tons of cargo followed shortly after. Once the exchanges were completed, I-29 turned eastward and U-180 turned back towards France. This experience was valuable to Kinashi when he, himself, finally set off for France in December 1943. In addition to his crew, he carried rubber, tungsten, tin, zinc, quinine, opium and coffee. He also had sixteen IJN officers, specialists and engineers on board. By 8th January 1944, the submarine had left Madagascar.

In early February, Kinashi received a signal from Germany to rendezvous with a U-boat that would upgrade I-29 with superior radar technology. On the 12th, he met U-518 southwest of the Azores. The Japanese submarine took aboard three technicians who installed a new FuMB 7 Naxos detector. Kinashi did not have to wait long to put his new equipment into action. While running along the surface off Cape Finisterre, Spain an RAF patrol plane equipped with a searchlight suddenly illuminated the water around I-29. Reacting with the decisiveness and speed gained through long experience, Kinashi crash-dived the submarine and escaped unscathed. Five days later, I-29 entered the Bay of Biscay, but Kinashi had arrived ahead of his escort and had to spend the night at the bottom of the sea. The next day, German forces escorted the Japanese submarine toward Lorient. Unbeknownst to Kinashi, however, he and his crew were not safe yet.

I-29’s schedule had been earlier decoded by the Allies. British aircraft were dispatched with the aim of sinking the submarine and its German escorts. They found the Yanagi mission off Cape Peas, Spain, but did not succeed in damaging I-29. Later that same day, the submarine and its escorts were attacked by more than ten Allied aircraft but, fortunately for Kinashi and his crew, all the bombs missed.

Cross-cultural encounters and Axis potential

After the two near misses, I-29 arrived at Lorient on 11th March and anchored safely next to Lieutenant Commander Max Wintermeyer’s U-190. Lorient was home to two U-boat flotillas, and the large number of veteran submariners set the scene for some lively cross-cultural encounters. On one occasion, German officers entertained the Japanese crew at a nearby bar. The bar’s rafters were inscribed with signatures of U-boat officers. Eager to get in on the act, I-29‘s Lieutenant Hiroshi Taguchi, Lieutenant Hideo Otani and several other officers added their own signatures to the rafters. After a 30,000 mile trip it must have felt good to make it to dry land and leave a mark of success!

The Japanese were treated to further German hospitality. Indeed, the entire crew were hosted at Château de Trévarez before a special train carried them onto Paris. While his crew enjoyed the sights, Kinashi travelled to Berlin and was decorated with the Iron Cross by the Führer himself. Ever the diligent workers, their German hosts busied themselves with the upgrades to I-29’s outdated anti-aircraft guns. They also loaded aboard:

A HWK 509A-1 rocket motor.

A Jumo 004B axial-flow turbojet.

Drawings of the Isotta-Fraschini torpedo boat engine.

Blueprints for jetfighters and rocket launch accelerators.

Plans for glider bomb and radar equipment.

A V-1 buzz bomb fuselage.

Acoustic mines.

Bauxite ore.

Mercury-radium amalgam.

Twenty more Enigma coding machines.

Hinting at the more frightening potential of greater Axis strategic collaboration, there is some evidence suggesting that I-29 carried a quantity of U-235 uranium oxide, one of the components needed to assemble an atomic bomb. Loaded with its vital military cargo, I-29 departed Lorient on 16th April.

On 14th July, I-29 passed through the Straits of Malacca and arrived at Singapore. Its passengers disembarked with their sensitive documents and proceeded by air to Japan. Most of the military cargo, however, remained aboard. Initially worried about the sub’s location, Allied code-breakers breathed a collective sigh of relief when they learned of I-29’s arrival in Singapore. Relief, however, quickly turned to alarm when an intercepted message between Berlin and Tokyo revealed the true value of the submarine’s cargo. Now alert to the terrifying potential of I-29’s mission, the Allies worked tirelessly to stop the submarine from reaching Japan.

The Allies were lucky when, on 20th July, Kinashi transmitted his proposed route for the last leg of the trip. The U.S. Navy deciphered the message, and the sub was sunk by torpedoes launched from the USS Sawfish. While the loss of the aircraft engines slowed the Japanese jet program, their blueprints, flown to Tokyo, arrived safely. They were used immediately to develop the Nakajima Kikka (orange blossom) and the Mitsubishi J8MI Shusui (sword stroke) – both based on German designs.

The sinking of I-52

Japan’s hope for further technological marvels now rested on Commander Kameo Uno and I-52, which had left Kure on 10th March 1944 (while I-29 was busy dodging Allied attacks near Brest). In its hold, Uno’s submarine carried strategic metals including molybdenum, tungsten, 146 bars of gold, as well as opium and caffeine. I-52 also carried fourteen passengers including engineers and technicians with ambitions of studying German weaponry. To avoid Allied spotter planes, Uno travelled submerged during the day and only surfaced at night.

After passing the Cape of Good Hope and entering the South Atlantic, on 15th May Uno sent his first message to Germany. By this time the British and Americans had broken the military codes of both Axis powers. Allied intelligence intercepted and deciphered Uno’s reports to Tokyo and Berlin, including his daily noon position reports. When I-52 entered the South Atlantic, the code-breakers quickly relayed its predicted route to a U.S. antisubmarine task force.

On 16th June, I-52 sent a coded transmission, giving its position away off the West African coast. The U.S carrier Bogue, equipped with fourteen aircraft, was ordered to track and destroy the sub. After arriving in the area where the Japanese were supposed to meet a German U-boat, the Americans began around-the-clock efforts to search for the Axis submarines. Although the skies were filled with American aircraft, Uno somehow managed to rendezvoused with Kurt Lange’s U-530 about 850 miles west of the Cape Verde Islands.

The Japanese commander welcomed a Lieutenant Schäfer on board to help navigate the last leg of his journey. Schäfer was accompanied by two petty officers who carried with them an improved radar. Bizarrely, the equipment fell into the sea during the exchange, but a dutiful Japanese crewman jumped in and managed to retrieve it. About two hours after meeting I-52, U-530 submerged and headed for Trinidad, leaving the three German officers aboard the Japanese sub. Again, we can only wonder how the two crews interacted with one another.

The day after his rendezvous with U-530, Uno, confident that he could take advantage of a stormy and moonless night to cloak his location, travelled along the surface in order to reach sooner the sanctuary of a German-occupied port. That evening, Allied forces picked up I-52 on their radar. Flares illuminated the area around the submarine and two 354-pound bombs were dropped, just missing I-52’s starboard side. Although Uno crash-dived and avoided the attack, his location was now compromised.

This game of submarine whack-a-mole could not go on forever. Sonobuoys, which detect underwater sounds, were deployed across a square mile of ocean. These were followed up with homing torpedoes which locked onto I-52’s propeller noises. After a long wait, the Allies heard a loud explosion. Another sonobuoy-torpedo combination later and the Allies got their desired outcome; a large oil slick at the site of the attack was spotted. Nearby, a ton of raw rubber bales bobbed along the surface of the water.

Meanwhile at Lorient, a German ship stood by ready to escort I-52, and diplomats scheduled to return to Japan waited anxiously for their ride home. With them at the dock were tons of secret documents, drawings and strategic cargo, which included acoustic torpedoes, fighter plane engines, radars, vacuum tubes, ball bearings, bombsights, chemicals, alloy steel, optical glass and one-thousand pounds of uranium oxide. The Germans also intended to improve I-52 with a snorkel. By 30th August, the Kriegsmarine finally presumed I-52 sunk.

The end of the Yanagi missions – a strategic oversight?

The question must be asked, why did the Yanagi missions stop? What happening to the initial excitement for military, scientific and strategic cooperation? The answer is a fairly simple one.

With the Americans closing in on the Home Islands and the final showdown of the Pacific war rapidly approaching, the IJN was compelled to devote every available resource to the defence of the Japanese mainland. After the failure of I-52‘s mission, it was no longer practical to send limited submarines on long, perilous journeys to Europe.

Reflecting back, what should we take away from the Yanagi missions? Although the missions are not remembered as much more than peculiar footnotes in the larger story of the Second World War, the threat of an exchange of nuclear materials and state-of-the-art technology was no doubt deemed important by the Allies – important enough for them to invest precious resources in locating, tracking and sinking the submarines before they could make their deliveries. The missions are scarcely known today, but at the time the threat they posed was clear.

The true importance of the Yanagi missions, however, lies in what I believe they represent. While we tend to think of their partnership as an uneasy ‘alliance of convenience’, the missions help us to imagine what Japan and Germany might have been able to achieve had they placed greater emphasis on joined-up, strategic coordination. Indeed, they represent a failure by the two Axis powers to think of the war beyond their own local, expansionist ambitions. Given the nuclear potential of the missions, we are perhaps fortunate that the Axis did not develop their partnership much beyond these largely overlooked submarine convoys.

What do you think of the Yanagi missions? Let us know below.

Now read Felix’s article on how Henry Ford tried to end World War One through diplomacy here.

Bibliography

https://www.warhistoryonline.com/instant-articles/japanese-and-germans.html

https://www.historynet.com/world-war-ii-yanagi-missions-japans-underwater-convoys.htm

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=6_4yaH6Y_hQ

Read more – on counterfactual history

https://camdenhistorynotes.com/2020/02/02/what-if-counterfactual-history/

Gavriel, R., 2002, ‘Why Do We Ask ‘What If?’ Reflections on the Function of Alternate History’, History and Theory, vol. 41, no. 4

Sustein, CR., ‘What If Counterfactuals Never Existed?’, The New Republic, 21 September 2014, accessed 27 February 2019, <https://newrepublic.com/article/119357/altered-pasts-reviewed-cass-r-sunstein>