Battered by wind gusts, the Avro Lancaster bucked and lurched as its crew struggled to keep the plane aligned with the signal fires set by the French Resistance fighters two thousand feet below. The “Lanc,” one of the Royal Air Force’s (RAF) workhorse bombers, was a homely beast. It had four noisy propellers, a protruding snout, and a pair of ungainly tail fins. Built to drop bombs four miles above Dusseldorf and Dresden, the Lanc was ill-suited for the stealthy parachute operation it was being asked to perform in the predawn hours over Occupied France.

Timothy Gay explains the story of Stewart Alsop.

A Lancaster like this one deposited Alsop’s Jedburgh team and an SAS unit over Occupied France in August ’44. Source/Attribution: Photo: Cpl Phil Major ABIPP/MOD, available here.

Instead of its usual payload of thousand-pound bombs, the plane was carrying 18 members of two separate cloak-and-dagger outfits. A three-man team – two Americans, one Frenchman – from the ultra-secret Jedburgh program had orders to buttress BERGAMOTTE, a Maquis (Resistance) operation charged with harassing enemy movements on the roads and railways of south-central France.

During their months of training, the Jeds had been taught to mimic the Maqui’s tactical mantra: Surprise! Mitraillage! Evanouissement! (“Surprise! Kill! Vanish!”) Their goal, a Jed team leader mused years later, was to make the enemy believe it was “fighting the Invisible Man.”

After pulling off an ambush with their French partners, the Jeds learned to yell: “Foutez le camp!” Roughly translated, it meant “Scram! Let’s get the hell out of here!”

For weeks, Allied intelligence had worried that the BERGAMOTTE cell was being hounded by the German secret police, the Gestapo. Indeed, the brass feared that the Gestapo had not only seized control of BERGAMOTTE’s radio but had compromised its entire operation. The three Jeds were warned that cutthroat German agents – not to mention turncoat Frenchmen, too – might be lurking to snuff any Allied operative parachuted in from England.

“We had been given to understand,” the Jed team was to observe in its after-action report months later, “that Mission BERGAMOTTE might conceivably turn out to be the Gestapo in sheep’s clothing.”

Trust no “sheep,” the Jeds were instructed. The most innocuous-looking French villager could be a Gestapo stooge; ditto the head of the Maquis cell from the next town over.

Each Jed was given a personal cipher – an idiosyncratic phrase – to be used in emergency wireless transmissions in the all-too-likely event that they became separated, or if the mission went sideways.

Also waiting to leap out of the plane were 15 members of a coup de main (hard-hitting special forces) group, the Third French Parachute Battalion of the British Special Air Services (SAS). Once behind enemy lines, the SAS “rogue warriors,” as British historian Ben McIntyre has tabbed SAS commandos, had their own agenda of mischief and sabotage. Their chief objective was blowing up a bridge along the Route Nationale, the region’s main north-south artery, to hobble the Germans’ capacity to mobilize troops and armor.

Since the Lanc had no benches, the 18 commandos were sprawled on its floor, cramped against the cigar-shaped supply cylinders that would soon be dumped over their drop zone. An eerie blue light from a single bulb suffused the cabin.

*

Nine full weeks after D-Day and just two days before the start of the “Champagne Campaign,” the Allies’ seaborne invasion of the Riviera, Adolf Hitler’s Wehrmacht had still not been ejected from France. The Lanc’s commandos were about to parachute atop thousands of trigger-happy German grenadiers and panicked Eastern European conscripts (Allied intelligence dismissively called them “Cossacks”), not to mention hundreds of members of the Milice, pro-Nazi Frenchmen who – it was now brutally clear – had backed the losing side.

The Milliciens knew that, if caught, they would pay for their treachery with their lives. They weren’t about to go down without exacting a bloodbath.

*

The Lanc’s unlikely first jumper, the 30-year-old American commander of the Jedburgh squad, had already crawled into position above the square hole carved aft of the plane’s bomb bay. His name was Stewart Johnnof Oliver Alsop. He was the scion of a Connecticut Yankee family whose ancestry could be traced to the Winthrops of Plymouth Plantation.

His facial features mirrored Hollywood matinee idol Robert Taylor’s: roguish blue eyes, an elongated patrician nose, mischievous eyebrows, and a mouth that always seemed to be suppressing a smile or a smirk. Even with a mop of brown hair hacked by military barbers, Alsop still radiated a Fitzgeraldian air of old money.

His mother, Corinne Robinson Alsop, was a niece of Theodore Roosevelt, a first cousin to First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt, and a distant cousin of Eleanor’s husband, Franklin Delano Roosevelt – or as Stewart’s father, a rock-ribbed Republican, called the president, “that crazy jack in the White House!”

A member of the Oyster Bay Roosevelt clan, Corinne had been equally disdainful of her Hudson Valley relation. When the young FDR came to Long Island to court Eleanor, Corinne derided him in her diary as a “feather duster” and hoped Eleanor would have the good sense to dump him.

The Alsops had been Republicans since the Whig Party disintegrated in the 1850s. Stewart’s old man, Joseph Wright Alsop IV, was a perennially frustrated Grand Old Party candidate for the Connecticut governorship. Stewart’s mother, a cofounder of the Connecticut League of Republican Women, had seconded the nomination of Alf Landon, her party’s 1936 presidential nominee. Despite Corinne’s stirring oratory, Landon carried only two states against her fifth cousin. Alas, neither of them was Connecticut.

Dining room debates between the elder Alsops and their more liberal offspring often ended with Pa braying at his kids to “go back to Russia!”

Stewart’s older brother by four years, Joseph Wright Alsop V, was already a respected columnist for the New York Herald Tribune and its national syndicate. With war looming in 1941, Joe volunteered for the U.S. Navy. He was serving in Burma as staff historian for aviator Claire Lee Chenault’s American Volunteer Group (later dubbed the “Flying Tigers”) when he was dispatched, in early December ‘41, to obtain supplies in Hong Kong. He was still in the city on December 7th and 8th, those nightmarish days when the Imperial Japanese military rampaged throughout the Pacific.

Joe shrewdly disposed of his uniform, borrowed civilian clothes, and pretended he was still an active correspondent. His ruse worked, sort of. For six months, the Japanese confined him to a detention camp for foreign noncombatants.

Corinne and Joseph IV, Ma and Pa as Stewart called them in his wartime letters, were never reticent about wielding their powerful connections. They pulled out all the stops to liberate young Joe, including petitioning that crazy jack in the White House. It worked: Joe was released in mid-’42 in a repatriation exchange of prisoners.

The Alsops were unrepentant Anglophiles, not surprising given their ancestral roots in the East Midlands and their allegiance to Endicott Peabody’s thoroughly British Groton School. As journalist Robert W. Merry noted decades later, “[The Alsops] always managed to get in the company of the high and the mighty throughout the world.” If their kin didn’t invent speaking with British affectation and a locked jaw, they helped perfect it.

Being high and mighty didn’t preclude Stewart from misbehaving at Yale. He got into hot water twice, once for pilfering all four hubcaps off a cop car, the other for getting caught with a young lady in his room. The second offense prevented him from graduating with his class.

Stewart had been in uniform prior to Pearl Harbor, but until ten days before his hush-hush mission to France, that khaki had belonged to His Majesty, not Uncle Sam. He had attempted on several occasions to join the U.S. Army but suffered from what his family labeled “white coat syndrome”: whenever a doctor armed with a sphygmomanometer was around, his blood pressure invariably spiked.

High blood pressure notwithstanding, Alsop was, along with a select group of other American Ivy League alums, invited by British bigwigs in the early fall of ‘41 to enlist in the elite King’s Royal Rifle Corps. The KRRC’s North American lineage had begun as the Royal American Regiment during the French and Indian War. When the upstart colonies fought to gain independence from the Crown, the regiment’s base was switched to the Caribbean, then Canada.

Its motto was Celur et Audax (“Swift and Bold”) – watchwords that rallied its riflemen from Waterloo to the Khyber Pass as they fought through the decades to safeguard the British Empire. The King himself served as the unit’s Colonel-in-Chief. KRRC’s “home” was the Hampshire city of Winchester and its fabled 900-year-old cathedral.

Among the other Americans ushered into the KRRC in ‘42 were future political commentator (and author of the memoir Eight is Enough); Tom Braden, a Dartmouth alum; another Dartmouth grad, Ted Ellsworth, who would go on to become a highly decorated infantry officer in both the British Eighth and U.S. First armies and survive a Nazi stalag; and George Thomson, a Harvard man whose service record would end up paralleling Alsop’s: the KRRC, the British Special Air Service (SAS), the British Special Operations Executive (SOE), the U.S. Office of Strategic Services (OSS), and, ultimately, the Jedburghs.

The very social KRRC didn’t care about such trifling matters as Alsop’s blood pressure. They did care, however, that these sons of American privilege bring their white dinner jackets for evening fêtes and their hunting rifles for England’s grouse season.

It turned out that Alsop didn’t don black or white tie all that often. Having completed more than a year of training in England, he survived Tunisia’s oppressive summer heat as one of General Bernard Montgomery’s Desert Rats after the Axis forces surrendered at Bizerte.

In the fall of ’43, the KRRC moved across the Mediterranean as the Allies slogged their way up Italy’s Tyrrhenian and Adriatic coasts. Alsop served as an infantry platoon leader in the British Eighth Army’s push along Italy’s eastern edge. In October, his KRRC Second Battalion was in Monty’s spearhead south of the River Trigno. At one point the Trigno skirmishing grew so fierce that Alsop and his platoon were forced to take refuge in a farmhouse.

A month later, the Second Battalion joined elements of the 8th Indian Division in leading Monty’s assault on Casa Casone, a German stronghold atop the River Sangro. It took two attempts and gruesome nighttime fighting before Casa Casone surrendered.

In December, Alsop and his fellow KRRC officer Thomson, then 25, sought transfers to the U.S. Army. But their repeated efforts were rebuffed in Tunisia and Egypt. For a time, the pair was in what Alsop described as “military limbo.”

Thanks to the connections of an English grande dame whose favor Thomson had cultivated in Cairo, the two briefly joined Britain’s hell-for-leather SAS before being transferred back to England in early ’44. Alsop and Thomson soon volunteered for the SOE, the clandestine intelligence service created by Prime Minister Winston Churchill to wreak havoc behind Nazi lines.

On August 3, 1944, Alsop was at long last granted his request to transfer to the U.S. Army. He was immediately assigned to the OSS, SOE’s American counterpart. Together, SOE and OSS had devised the Jedburgh commando program to help Resistance fighters in France and the Low Countries disrupt the Wehrmacht before, during, and after the Allies’ cross-channel invasion. Some four dozen Jedburgh missions had already jumped off to Occupied Europe by the time Alsop’s Lanc went airborne.

Alsop was still getting used to be being called “Loo-tenant” after being addressed as “Leff-tenant” for more than a year. He also had to remind himself that American soldiers saluted their superiors with a straight-edged right hand, as opposed to the British Army custom of a flat-hand-to-the-forehead, part of an elaborate ritual that included stamping both feet and emitting a full-throated “Sir!,” which, given the accents involved, often came out more like “Suh!”

In the pell-mell rush to get ready for the Jedburgh jump, there had not been time for Alsop to requisition a U.S. Army uniform, so he borrowed one from his younger – and considerably shorter and chunkier – brother John, a former military policeman then also in training as a Jedburgh commando. Stewart continued to wear his KRRC insignia, his British marksmanship medals, his Mediterranean campaign ribbons, and his SAS wings on his ill-fitting American garb – a curious decision that, a few weeks later in the wilds of France, caused enough confusion in the mind of an American lieutenant colonel to nearly get Alsop shot as an enemy spy.

The dashing 30-year-old with the impeccable pedigree was about to hit the silk wearing an outfit that made him look like an unkempt schoolboy.

*

Little about Stewart Alsop’s breeding hinted that he’d make a kick-ass commando in a war to save the world from fascism. The Alsops may have been longtime fixtures in effete America, with tentacles that seemed to reach everywhere, but they didn’t exactly have a reputation for martial heroics.

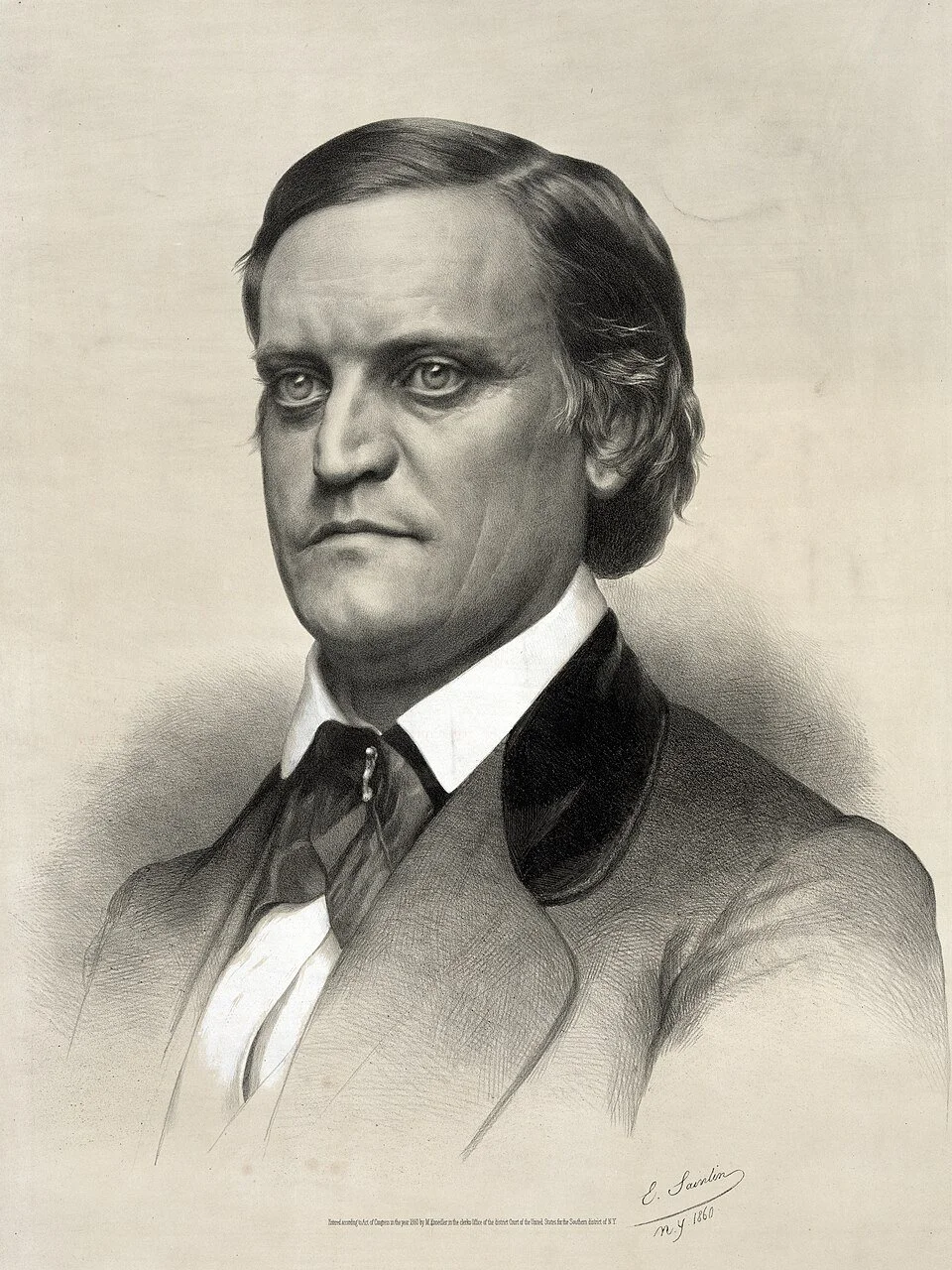

In the 1960s, the Saturday Evening Post commissioned Stewart, then its Washington columnist, to research and write about his family heritage. He learned that Joseph Wright Alsop I, his great-great-grandfather, paid for someone to take his place in George Washington’s Continental Army. Eight decades later, that same dodge was repeated by Joseph Wright Alsop III, who managed to evade service in Abraham Lincoln’s Grand Army of the Republic by hiring a surrogate.

Indeed, as far as Stewart could tell, no forebear named Alsop had ever served as a soldier.

“It was not so much that my ancestors were cowards, though no doubt some of them were,” he wrote years later. “They just hated the idea of being in a subordinate and dependent position.”

Perhaps it was that wariness that compelled one John Alsop, a New York delegate to the Second Continental Congress in 1776, to balk at signing a little document known as the Declaration of Independence. John Alsop managed to pull a reverse “John Hancock”; in Alsop family lore, he was known as “John the Non-Signer.”

Past and future Alsops never declined opportunities to fatten their pocketbooks, however. Like so many New England colonial families, the Alsops, then living in the Connecticut seaport Middletown, made their fortune in West Indies trade. Alsop ships carried ice and other commodities south to the Caribbean, then peddled barrels of rum back home. They also dabbled in triangular trade with China and England, bringing back to the colonies coveted plate ware – and perhaps, Stewart coyly hinted in his memoirs, some opium, too.

*

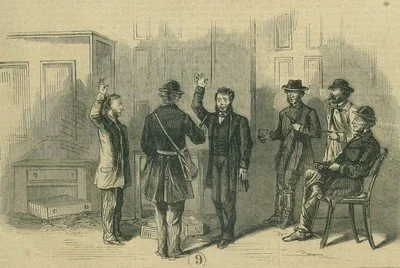

One hundred sixty-eight years, one month, and nine days after an Alsop refused to sign Thomas Jefferson’s Declaration, Stewart Alsop found himself enmeshed in a Jedburgh mission bollixed up from the get-go. When the three Jeds arrived the evening of August 12, 1944, at the RAF’s Tempsford Airfield some 50 miles northeast of London, no one was expecting them.

“It soon became apparent,” Alsop wrote in his after-action report, “that no one had the faintest notion who we were or what to do with us, and that furthermore no one was particularly interested.”

He and his Jed mates had to scramble to find their plane, which turned out to be a Lancaster planted on the runway, already revving its engines. It was crewed by Canadian airmen about to take off on their first sortie (ever!) over enemy territory. Moreover, they’d had no training in parachute operations – a pair of disquieting facts probably not shared with the Jeds as they climbed aboard.

Most of the SAS men were already jammed into the cabin. Two other sticks of SAS paratroopers were on different planes warming up at Tempsford. The three planes were supposed to fly together to execute a coordinated drop in the Limoges-Périgeux corridor of central France’s Creuse Department, a hilly region that for weeks had been besieged by a Wehrmacht offensive targeting the Resistance.

“Maquis Creuse kaput!,” German soldiers had bragged to French villagers, dragging their fingers across their throats. Far from kaput, BERGAMOTTE principals had been alerted by London to ignite their signal fires some two hours after midnight on August 13th.

Somehow, the jump master expert at pinpointing when and where special ops paratroops should be released over hostile turf failed to show up. He was replaced by a corporal, a nervous rookie unfamiliar with the RAF methodology for low-altitude drops: a sequence of flashing red and green lights accompanied by a series of commands – “Action Stations! . . . Running In! . . . Number One, Go! . . . Number Two, Go! . . .”

Poised to jump immediately after Alsop were the two other members of his Operation ALEXANDER Jedburgh team: a St. Cyr-trained lieutenant and saboteur named Renè de la Tousche, whose nom de guerre (to protect his family in the event he was captured or killed behind Nazi lines) was Richard Thouville; and a 19-year-old sergeant and radio operator from Montclair, New Jersey, named Norman “Dick” Franklin.

Each was carrying an M-I carbine, a Colt revolver, an entrenching tool to bury his parachute, a large knife, a string of grenades, a canteen, a first aid kit, an E&E (Escape and Evasion) kit with camouflaged silk maps of south-central and southwestern France, a tiny compass, a little knife that looked like a razor, a wire for garroting enemy sentries, a fishing line and hooks in case other food sources failed, a packet of amphetamines to stave off sleep, a chocolate bar, a pack of cigarettes, and a small flask of brandy.

Their pre-mission briefing a few days earlier had taken place in a glass-encased room on the highest floor of a “safe house” in London. They were perched above the surrounding buildings and could glimpse the tops of the trees in Hyde Park. In mid-meeting, Franklin spotted an airborne V-1 buzz bomb. Just after it passed overhead, its motor stopped – then the most ominous sound in London, because it meant an imminent plunge and explosion. Seconds later, the doodlebug detonated in the park.

The three of them had bonded during months of training at Milton Hall, a rambling Cambridgeshire manor that SOE and OSS had taken over for special ops prep. “Milton Hall was a fantastic Elizabethan pile, country seat of an old, aristocratic, and formerly exceedingly rich English family,” Alsop and Braden wrote after the war in their book, Sub Rosa. Among many other arduous tasks, Jed trainees were obligated to make eight practice parachute jumps and do plenty of cardiovascular work.

On long-distance runs in the East Anglian countryside, Alsop would look around, determine that no superior officers were extant, and declare to Thouville and Franklin, his handpicked charges, that it was time to “relax-ey-vous.”

The trio would slip behind a stonewall or a hedgerow and swap stories and smokes. When Thouville reminded Alsop that “relax-ey” was not a real French verb, the American feigned outrage and snapped something like: “Well, dammit, it ought to be!”

Thouville’s métier in these sessions was an apparently bottomless cache of bawdy jokes about French clerics and their parishioners, delivered in a combination of broken English and snarky French. With each telling, Thouville’s gags got more hilarious, Franklin remembered in his unpublished memoir.

Alsop’s comrades were amused that someone with such a patrician background could be so playful and irreverent. The Connecticut Yankee would readily concede that his upbringing had made him class-conscious – and to a fault. But he took exception if anyone accused him of being pompous.

“Stuffy, yes,” Alsop would admit, impish eyes twinkling. “But pompous? Never!”

Early on, Alsop had made the mistake of telling his American KRRC buddies that his surname was properly pronounced with a soft “a,” as in “ball,” not a hard “a,” as in “pal.” Instantly, of course, he was dubbed “Al,” a screw-you moniker that stuck with him through the war. After that gaffe, he was gun-shy about discussing his famous family: It took him a half-year to own up about being related to the Roosevelts.

The three Jeds had been rehearsing their parachute drop for months, on top of every other move they would need to survive a long stretch behind enemy lines, from learning colloquial French and studying Gaullist vs. Communist Resistance politics to mastering Jiu Jitsu hand-to-hand combat and teaching Maquis fighters how to operate mortars and makeshift radios.

Alsop’s codename was “Rona.” Franklin’s was “Cork.” Thouville’s was “Leix.”

On three previous occasions in early August, Rona, Cork, and Leix had been called to an East Anglian airfield and told their operation would launch that night. Each time, the mission had, for one reason or another, been scrubbed. But the fourth time, despite the logistical challenges, they went wheels-up just after 10 p.m.

Some 90 minutes into the flight, somewhere over southern Normandy, the Lanc began to rear “like a startled horse,” Alsop remembered. “Le flak!” Thouville shouted into Alsop’s ear.

While on the front lines in Italy, Alsop had been shot attacked by rifles, machine guns, mortars, aerial bombs, and 88’s, the Germans’ deadly artillery weapon. But this was his first experience with an ack-ack assault. It felt, Alsop recalled, like a violent thunderstorm – except a lot more dangerous. Franklin, the radioman, likened flak to “someone beating a large tin pan with a wood spoon.”

Bloodred tracers appeared out of nowhere, followed by deafening explosions that seemed to happen beneath both wings. Just when they thought the Lanc was out of range, another fusillade would erupt. Amid one barrage, Alsop looked around at his fellow commandos: To a man, they were protecting their crotches.

Once the plane cleared Normandy, the flak began to recede. By then, the other two planes in the formation had scattered. The neophyte Canadians were flying solo.

A half-hour or so later, the Lanc’s airmen thought they had zeroed in on the correct Resistance bonfires in the fields southwest of the Creuse Department’s Monts de Guéret, the Drop Zone (or “Dee Zed,” in British military parlance) for both Team ALEXANDER and the SAS squad. But turbulence kept knocking the Lanc off course.

One minute the crew would have the L-shaped fires in sight; the next they would disappear. Wrestling with the controls, the pilots took a couple of passes over what they surmised was the Dee Zed.

The rookie jump master got more nervous with each pass. Before leaving British airspace, the Jeds had tried to teach the “Action Stations!” progression to him. But now it seemed too complicated.

“Look, chaps,” Alsop remembered the corporal yelling above the din. “I’ve never done this before, and I don’t want to get it wrong!”

The dispatcher hollered to Alsop that he would flash a single red light – and that as soon as Alsop saw it, he should drop through the hole. Alsop nodded and shouted for Thouville and Franklin to get ready.

Thouville bleated, “J’ai une trouille noire,” into Alsop’s ear. Yeah, I’m a little black hole, too, Alsop chuckled.

Alsop tried hard to remember what he’d learned in those eight practice jumps: “Hold straight, head on chest, legs together, pull the webs, don’t reach out for the ground. . .”

As they’d been taught, Thouville wrapped his legs around Alsop’s neck and shoulders; Franklin did the same to Thouville’s. The SAS guys crept closer to the hole.

*

His legs dangling out of the Lanc, Alsop’s thoughts surely drifted to the bride he’d left behind in London. He had been married, for all of 54 days, to a beguiling Yorkshire lass 12 years his junior named Patricia “Tish” Hankey.

They had met two years earlier, in August 1942, when Alsop and his smooth-talking KRRC pal Thomson had somehow wangled invitations to a soiree being held at the Yorkshire estate of England’s Premier Baron, the nobleman at the top of the peerage pyramid. To their delight, they discovered that real American-style martinis – not the watered-down British imitations – were being served at the party. Even better, a pair of attractive young Englishwomen were swilling the gin-and-vermouth with abandon. Even better yet, the women appeared to be returning the Americans’ glances.

Thomson deftly handled the introductions. The taller of the two girls informed Alsop, whose hair had just been buzzed by a KRRC barber, that he “looked like a criminal,” which Alsop viewed as an encouraging flirtation.

With their lipstick, rouge, and martini-guzzling, the women appeared to be in their early twenties. They weren’t.

The belle Thomson was eyeing turned out to be the baron’s 18-year-old daughter, Bee. Tish, the object of Alsop’s attention, was only 16, an unsettling fact that Alsop discovered only after he finagled a midnight kiss in the garden – or so he claimed in his memoirs. Alas, their embrace was witnessed by the Premier Baron himself, who promptly ratted them out to his wife, who in turn blew the whistle to Tish’s parents.

The baron’s censure got their romance off to a rocky start. Despite her parents’ disapproval and Alsop’s prolonged absence in the Mediterranean, they pined for one another. When Alsop resurfaced in Britain in early ‘44, they were determined to get married.

Still, it took Alsop months to convince Tish’s stodgy father and her devoutly Catholic mother to let their daughter wed a considerably older Protestant Yank. Despite his lofty American relations, Alsop was a man of (relatively) humble means. In prewar New York, he had earned a modest salary editing books for Doubleday.

The deliberations with Tish’s father turned testy, but Alsop was smitten; he refused to take “no” for an answer. Her father relented, but only after making Alsop jump through hoops to guarantee his daughter some measure of financial security should he perish in France. With the cross-Channel invasion then going full throttle, “Alsop, S., Lt., KIA” was a distinct possibility. The Hankeys had already lost a son (by coincidence, he had also served in the KRRC) to Hitler’s Afrika Korpsin Libya; they didn’t want their daughter widowed while still a teen.

Tish and Stewart nevertheless took their vows exactly two weeks after D-Day in a side altar at St. Mary’s Catholic Chapel in Chelsea. The main altar had not recovered from the bomb damage it suffered four years earlier during the Blitz, a blast that killed 19 locals sheltering in its crypt that night.

Both the wedding ceremony and their reception in a top-floor suite at The Ritz (a boozy affair underwritten by Stewart’s brother-in-law, Percy Chubb, of the Connecticut insurance family) were interrupted by V-1 rocket attacks. At one point, the revelers raced up a stairwell to The Ritz’s rooftop to watch buzz bombs zoom over Piccadilly. Fortunately for the Jedburgh program and future Alsop progeny, the doodlebugs missed Mayfair – at least that day.

Allied intelligence, of course, forbade Stewart from sharing details of his mission to France – or even acknowledging the existence of the Jedburgh program. Tish, therefore, knew little of her new husband’s special ops background.

Intrigue and subterfuge, however, cut both ways. For a year-and-a-half prior to their wedding, Tish had worked sub rosa at wartime London’s spy central, the art deco structure at 55 Broadway SW1 in the heart of Westminster. Her building shared secrets with its dingy cousin across the street, 54 Broadway, the headquarters of Britain’s spy chief Stewart Menzies and scores of espionage and sabotage specialists, all plotting the destruction of Hitler’s Reich.

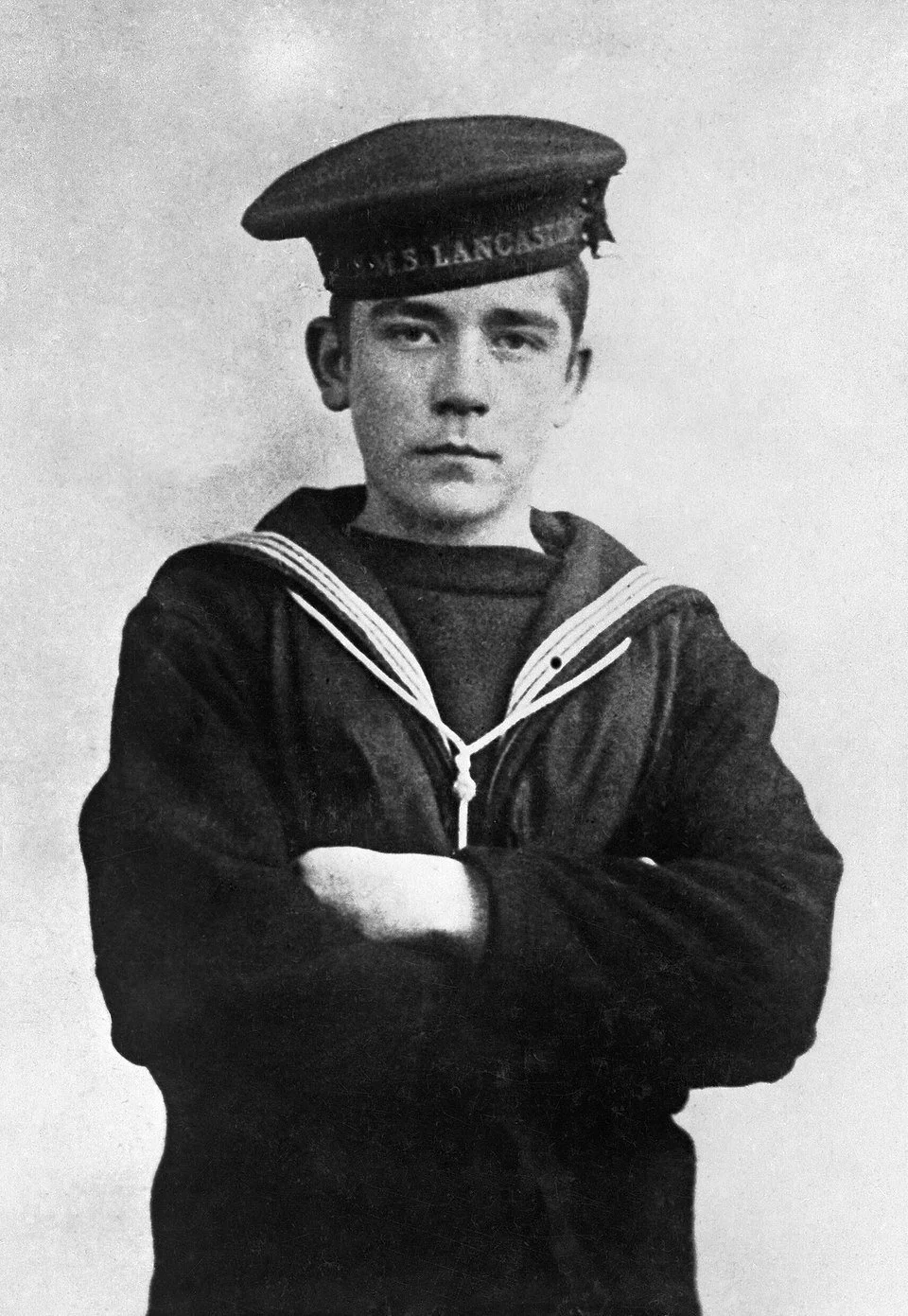

Tish had been, since the day she turned a precocious 17 (!), a naval decoding analyst for MI5, Britain’s counterintelligence agency. In early April 1944, her 13th month on the job, she received a message from the Home Fleet that the methodically planned Operation TUNGSTEN had succeeded: in a sneak attack off the Norwegian coast, Germany’s über-battleship Tirpitz had been decimated by British carrier planes.

The news triggered jubilation on both sides of Broadway, at 10 Downing Street, at Whitehall’s cabinet offices, at Bletchley Park’s codebreaking station, and at the Supreme Headquarters of the Allied Expeditionary Forces (SHAEF) in South London’s Bushy Park.

When Tish, then barely 18, raced up several flights of stairs to share the news with her friend Bee, a fellow MI5 decoder, the two of them jumped up and down, then danced a little jig.

Tish and her new husband didn’t completely fess up about their respective derring-do until after the war. No wonder their daughter, writer Elizabeth Winthrop Alsop, called her 2022 memoir, Daughter of Spies.

Just days before obtaining his long-awaited commission in the U.S. Army, Alsop had gotten news that he’d earned an elevation to captain in the British Army. The transfer came with a catch: if he wanted to join the Yanks, he’d have to accept a demotion in rank back to lieutenant. But pay in the U.S. Army dwarfed the Brits. Alsop would make a lot more as a Yank lieutenant than as a Tommy captain. He took the transfer.

Tish helped her new spouse pin his American lieutenant’s bars on the shoulder pads of his borrowed uniform. When Franklin saw them, he chortled and informed his boss that the bars were turned the wrong way.

There was another secret that Tish may have been keeping from Stewart in the second week of August 1944: she was already pregnant.

*

More anxious minutes passed inside the Lanc. Alsop remained fixated on reacting to the dispatcher’s signal. The plane continued to fight the wind.

Alsop, Thouville, and Franklin couldn’t be certain, but it felt like the Lanc was flying in aimless circles. They worried that every German soldier and hostile mercenary in a 30-mile radius was now on full alert. If the commandos didn’t jump soon, the crew would have no choice but to head back to England. Given the enemy’s ack-ack guns, flying over the Normandy battlefield after daybreak would have been in Alsop’s reckoning, “suicide.”

Suddenly, a light flashed inside the plane. Alsop didn’t hesitate or double-check with the jump master. He wriggled through the hole and pushed hard with both hands. Off he plummeted into a moonlit French night.

As soon as his chute jolted open, he knew he’d made a mistake; the plane was flying too high and too fast. To avoid detection, Allied commandos had been trained to jump at 800 feet from a stalled-out aircraft; the Lanc, Alsop sensed, was flying at a height at least double the desired altitude. It was traveling so fast, moreover, that Alsop could feel thewhoosh from the prop wash – not the way a jump from a semi-static craft was supposed to feel.

Alsop looked up. The parachutes of Thouville and Franklin were nowhere to be seen.

He later learned that the jump master had flipped on his flashlight to fish out a cigarette. Alsop mistook the corporal’s nicotine fix for the “Go!” signal; the American had leapt out of the plane way too early. The horrified dispatcher restrained Alsop’s comrades from following their commander out the hole.

Hurtling toward the ground, Alsop craned his neck in three directions but couldn’t see the Resistance reception committee signal fires. A mission fraught with danger had suddenly gotten even more perilous.

Alsop could hear dogs barking – probably not the best omen, he remembered thinking. “Even before I hit the ground, I realized that I had been a damn fool,” he was to write.

Seconds later, he thudded into the edge of a wooded area. His chute got tangled in a small tree. It turned out to be fortuitous; he found himself hanging just inches off the ground.

He slithered out of his harness and touched French soil for the first time in the war. While behind German lines over the next three months, Alsop and his men would collude with merciless Maquis leaders; hector enemy convoys; help liberate a host of villages; throttle the Wehrmacht’s capacity to move; bivouac in the woods some nights and bunk in lavish chateaus on others; patch up differences (at least temporarily) between rival Resistance leaders; watch in amazement as French fighters and clerics unearthed rifles that had been hidden months earlier in cemetery graves; hear wild stories about German paratroopers trying to infiltrate Allied and Resistance strongholds while disguised as French priests; uncover a supposed Nazi superweapon unknown to Allied intelligence; and be toasted as heroes almost everywhere they went.

Maquisards came to respect Alsop so much they nicknamed him the “Commandant Americain.” Somehow, the Commandant and his two Jed subordinates lived to tell their tale.

But with his parachute snared in a tree, Alsop’s first moments as a guerilla fighter did not get off to an auspicious start. He frantically tried – and failed – to free his chute from the tree. The mission had barely begun, and he’d already managed to mess up two core Jedburgh rules: Never leave your men behind and never leave your chute exposed.

He snuck behind a big bush, lit a cupped cigarette, took a tug on his brandy, and surveyed the situation. His next moves were not readily apparent; there were no good options.

Squinting through the moonlight, he could make out what he thought was a hamlet not far down a dirt road. His best chance of survival, he decided, would be to sneak into town, knock on a door, and pray that its occupants were friendly to the Allied cause and not peeved about being rousted out of bed in the middle of the night by a Yank officer with an uneven grasp of French.

He stubbed out his cigarette and began inching down the path, his head on a swivel. All the sudden, the dog yapping started up again, but this time louder and more conspicuous.

“Keee-riiist!” he recalled thinking. “How could the German army not hear that?!”

Alsop retreated to the same bush, took a big swig from his flask, and lit another smoke. At this rate, the pack would be gone before sunup. So would his brandy.

Three decades later, he wrote, “I was entirely alone in Occupied France. I was in [an] American army uniform. I had no idea where I was.”

“Face it, Alsop,” he muttered aloud. “You’re in trouble.”

Timothy M. Gay is the Pulitzer-nominated author of two books on World War II, two books on baseball history, and a recent biography of golfer Rory McIlroy. He has written previous WWII-related articles for the Daily Beast, USA Today, and many other publications.