In the twilight of the 19th century, the world watched as China convulsed in a tumultuous uprising known as the Boxer Rebellion. This cataclysmic event, which erupted in 1900, was not merely a clash of arms, but a collision of civilizations, ideologies, and ambitions. At its core, the Boxer Rebellion was a struggle for the soul of China, pitting traditional values against encroaching foreign influence.

Here Terry Bailey delves into the multifaceted dimensions of the rebellion, outline the foreign powers involved, their political aims, the valor recognized through decorations like the Victoria Cross and Congressional Medal of Honor, and the perspectives of the Chinese Boxers, including the pivotal role played by Empress Dowager Cixi.

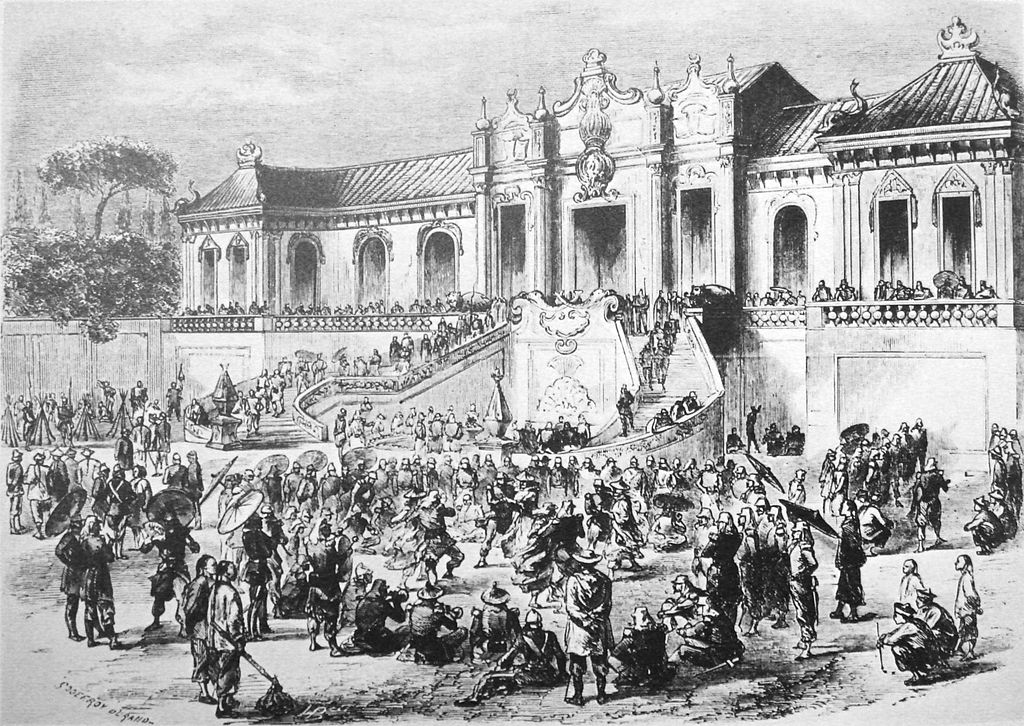

The photo shows foreign forces inside the Forbidden City in Beijing in November 1900 during the Boxer Rebellion.

Origins of the Boxer Movement

To comprehend the Boxer Rebellion, one must understand its roots deeply entwined with China's history of internal strife and external pressures. The late 19th century saw China reeling from a series of humiliations at the hands of foreign powers, compounded by internal turmoil and economic distress. The Boxers, officially known as the Society of Righteous and Harmonious Fists, emerged as a grassroots movement fueled by resentment towards foreign domination and perceived cultural erosion.

The International Response

As the Boxer movement gained momentum, foreign nationals and missionaries in China became targets of violent attacks, triggering international alarm. In response, an Eight-Nation Alliance composed of troops from Austria-Hungary, France, Germany, Italy, Japan, Russia, the United States and the United Kingdom intervened to quell the rebellion and protect their interests in China.

Each member of the alliance had its own political aims and agendas driving their involvement in the conflict. For instance, European powers sought to safeguard their economic privileges and spheres of influence in China, while Japan seized the opportunity to assert its growing regional power. The United States, keen on preserving its ‘Open Door Policy’ and ensuring the safety of American citizens, also joined the intervention force.

The Boxers' Perspective

Contrary to portrayals by Western accounts, the Boxers were not merely mindless fanatics but individuals driven by a complex blend of nationalism, religious fervor, and socio-economic grievances. Comprising primarily of peasants and martial artists, the Boxers perceived themselves as defenders of Chinese tradition against the encroachment of Western imperialism and Christian missionary activities.

For the Boxers, their struggle was not just against foreign powers but also against the corruption and decadence of the Qing dynasty. Their rallying cry, "Support the Qing, destroy the foreigners," encapsulated their belief in restoring China's glory by expelling foreign influence and purging the nation of perceived traitors.

Empress Dowager Cixi's Role

At the heart of the Boxer Rebellion stood Empress Dowager Cixi, a formidable figure whose political maneuvering would shape the course of Chinese history. Initially hesitant to openly support the Boxers, Cixi eventually threw her support behind the movement, viewing it as a means to bolster her own waning authority and expel foreign influences.

Cixi's decision to align with the Boxers proved fateful, leading to a declaration of war against the Eight-Nation Alliance. Despite her efforts to galvanize Chinese forces, the coalition's superior firepower and logistical prowess ultimately overwhelmed the Boxer forces and brought about the collapse of their rebellion.

Legacy of the Boxer Rebellion

The Boxer Rebellion left an indelible mark on China and the world, reshaping geopolitical dynamics and fueling nationalist sentiments. While the intervention of the Eight-Nation Alliance temporarily quelled the uprising, it also deepened China's resentment towards foreign powers and sowed the seeds of future conflicts, in addition to further internal strife.

The rebellion's aftermath witnessed the imposition of harsh indemnities on China, further weakening the Qing dynasty and hastening its eventual collapse. The events of 1900 served as a stark reminder of the perils of imperialism and the enduring struggle for national sovereignty.

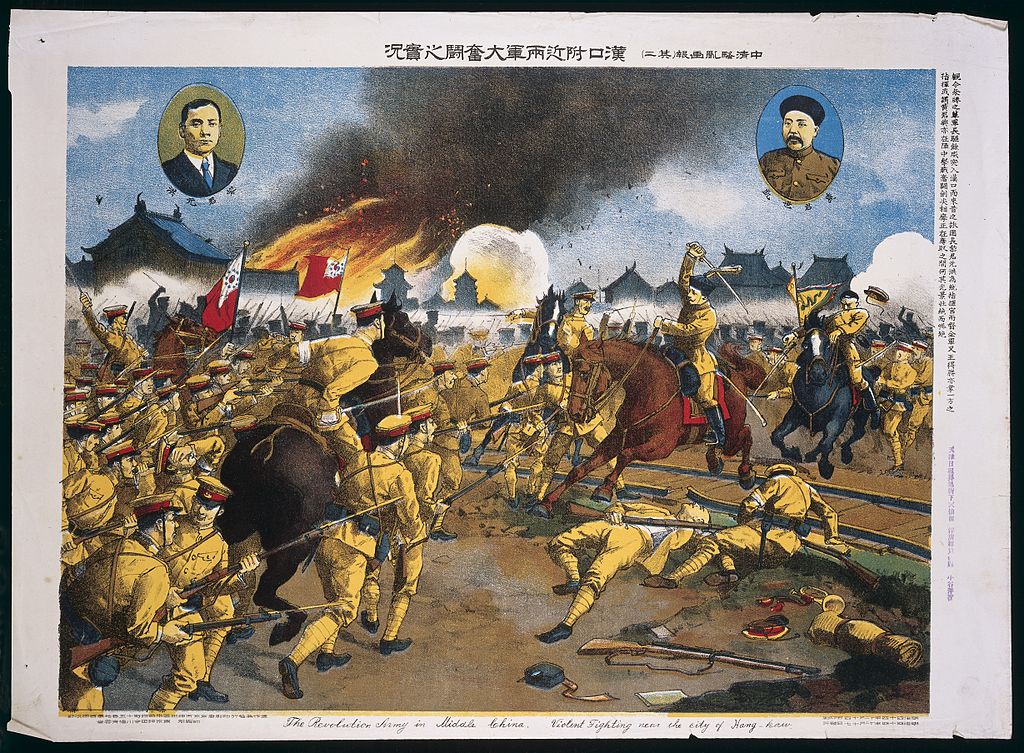

Sun Yat-sen, known in China as Sun Zhongshan was the eventual galvanized the popular overthrow of the imperial dynasty through his force of personality. Which occurred on the 19th of October 1911. At the time of the eventual successful overthrow of the 2000 year old dynasty Sun Yat-sen was in America attempting to raise funds for the future of China.

He was a highly educated individual who was strongly opposed to the actions of the Boxers before and during the rebellion, knowing that violent offensive action against the strong foreign powers would be detrimental to China’s future.

In conclusion

The Boxer Rebellion is an outstanding example of the complexities of history, where competing interests, ideologies, and aspirations converge in a crucible of conflict. Reflecting on this turbulent chapter, it is possible to be reminded of the enduring quest for dignity, autonomy, and justice that transcends borders and generations.

Additionally, the history of the Boxer rebellion should provide a stark reminder for any nation that decides to intervene into another nation’s concerns where the intervening power has hidden political agenda residing below the surface.

This reminder should be dealt to all nations, not only where a political fueled agenda influences an intervention by military force but any intervention that the preservation and protection of life is not the prime concern of military action.

“war is a continuation of politics by other means,”

Carl Philipp Gottfried von Clausewitz, 1st of July 1780 – 16th of November 1831

Find that piece of interest? If so, join us for free by clicking here.

Victoria Cross and Congressional Medal of Honor Recipients

The Boxer Rebellion witnessed acts of exceptional bravery and heroism, recognized through prestigious military decorations such as the Victoria Cross and Congressional Medal of Honor, for soldier of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and the United States of America.

Victoria Cross recipients

General Sir Lewis Stratford Tollemache Halliday VC, KCB

General Sir Lewis Stratford Tollemache Halliday VC, KCB (14th of May 1870 – 9th of March 1966) was an English recipient of the Victoria Cross, the highest and most prestigious award for gallantry in the face of the enemy that can be awarded to British and Commonwealth forces.

Rank when awarded VC (and later highest rank): Captain RMLI, (later General)

His citation reads:

Captain (now Brevet Major) Lewis Stratford Tollemache Halliday, Royal Marine Light Infantry, on the 24th June, 1900. The enemy, consisting of Boxers and Imperial troops, made a fierce attack on the west wall of the British Legation, setting fire to the West Gate of the south stable quarters, and taking cover in the buildings which adjoined the wall. The fire, which spread to part of the stables, and through which and the smoke a galling fire was kept up by the Imperial troops, was with difficulty extinguished, and as the presence of the enemy in the adjoining buildings was a grave danger to the Legation, a sortie was organized to drive them out.

A hole was made in the Legation Wall, and Captain Halliday, in command of twenty Marines, led the way into the buildings and almost immediately engaged a party of the enemy. Before he could use his revolver, however, he was shot through the left shoulder, at point blank range, the bullet fracturing the shoulder and carrying away part of the lung.

Notwithstanding the extremely severe nature of his wound, Captain Halliday killed three of his assailants, and telling his men to "carry on and not mind him," walked back unaided to the hospital, refusing escort and aid so as not to diminish the number of men engaged in the sortie.

Commander Basil John Douglas Guy VC, DSO

Commander Basil John Douglas Guy VC, DSO (9th of May 1882 – 29th of December 1956) was an English recipient of the Victoria Cross, the highest and most prestigious award for gallantry in the face of the enemy that can be awarded to British and Commonwealth forces.

Rank when awarded VC (and later highest rank): Midshipman RN, (later Commander)

London Gazette citation

“Mr, (read Midshipman), Basil John Douglas Guy, Midshipman of Her Majesty’s Ship “Barfleur”.

On 19th July, 1900, during the attack on Tientsin City, a very heavy cross-fire was brought to bear on the Naval Brigade, and there were several casualties. Among those who fell was one A.B.I. McCarthy, shot about 50 yards short of cover.

Mr. Guy stopped with him, and, after seeing what the injury was, attempted to lift him up and carry him in, but was not strong enough, so after binding up the wound Mr. Guy ran to get assistance.

In the meantime the remainder of the company had passed in under cover, and the entire fire from the city wall was concentrated on Mr. Guy and McCarthy. Shortly after Mr. Guy had got in under cover the stretchers came up, and again Mr. Guy dashed out and assisted in placing McCarthy on the stretcher and carrying him in.

The wounded man was however shot dead just as he was being carried into safety. During the whole time a very heavy fire had been brought to bear upon Mr. Guy, and the ground around him was absolutely ploughed up.

Congressional Medal of Honor Recipients

During the Boxer rebellion, 59 American servicemen received the Medal of Honor for their actions. Four of these were for Army personnel, twenty-two went to navy sailors and the remaining thirty-three went to Marines. Harry Fisher was the first Marine to receive the medal posthumously and the only posthumous recipient for this conflict.

Side note:

Total number Victoria Crosses awarded

Since the inception of the Victoria Cross in 1856, there have been 1,358 VCs awarded. This total includes three bars granted to soldiers who won a second VC and the cross awarded to the unknown American soldier.

The most recent was awarded to Lance Corporal Joshua Leakey of 1st Battalion The Parachute Regiment, whose VC was gazetted in February 2015, following an action in Afghanistan on 22nd of August 2013, this information was correct at the time of writing.

Total number of Congressional Medal of Honor, (MOH), awarded

Since the inception of the MOH in, 1861 there have been 3,536 MOH awarded.

The most recent was awarded was made to former Army Capt. Larry L. Taylor during a ceremony at the White House, by President Joe Biden, Sept. 5, 2023, this information was correct at the time of writing.

The Medal of Honor was introduced for the Naval Service in 1861, followed in 1862 a version for the Army.