In this article, as our part of our American Revolution season, we look at the life of a British soldier during the American Revolutionary War.

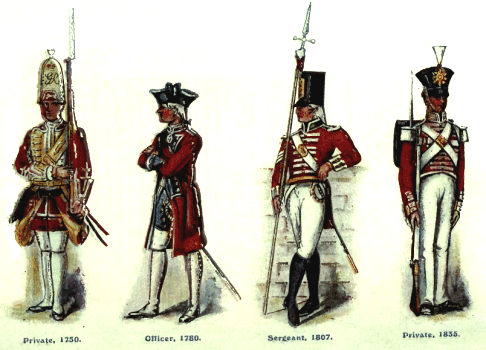

British army redcoats through the ages.

Source: Regimental Nicknames and Traditions of the British Army, London: Gale & Polden, 1916.

Army muster rolls in general provide an overview of each soldier's career, allowing each man to be traced from the time that he joined his regiment to the time he left it. Occasionally, however, a soldier enigmatically appears on the rolls without any indication of where he came from, and sometimes men disappear from the rolls with no explanation of where they went. Benjamin Reynard, a grenadier in the 37th Regiment of Foot, provides an example of both of these nuances.

Reynard served in America, but it is not clear when he joined the army or arrived on the west side of the Atlantic Ocean. He first appears on the roll of the grenadier company covering the period 25 December 1777 through 24 June 1778. Most men who joined grenadier or light infantry companies had served for at least a year in other companies of the regiment (there were occasional exceptions, particularly for men who had prior military experience). There is no annotation on this roll that he joined the company during that muster period, and no trace of him on the rolls of other companies during preceding periods. Admittedly, more detailed analysis might resolve this mystery; sometimes there are significant changes in the ways that names are spelled from one roll to another, and sometimes even the man's first name changes (for example, there's a chance that Benjamin Reynard is the 'Thomas Raynor' who appears on the prior roll of the same company), but determining this requires careful tracing of all of the names on the rolls, a long and tedious process.

Reynard continues on the rolls of the grenadier company of the

37th Regiment through August of 1783. At that time, the regiment was

reorganized due to force reductions at the end of the war; the strength was

reduced from ten companies to eight, and many men were discharged. Reynard

appears on a set of rolls covering the period 24 June through 24 August (an

unusual muster period), but is absent from the subsequent roll covering 25

August through 24 December. Again, it is possible that his name is not obvious

because of spelling permutations, but the spelling is very consistent on all of

the interim rolls.

Although we lack career details on Reynard that we have for most soldiers,

there survives a record of a personal vignette during Reynard's American

service, something we lack for most soldiers. At the beginning of June 1779 the

grenadier battalion that included his company was part of an expedition that

fortified posts on the Hudson River north of New York city including Stony

Point on the west shore and Verplanck's Point on the east shore. They camped in

wigwams made of brush, a typical practice for the British army in America. On 4

June they fired a salute in honor of the King's birthday.

At about 10 AM on 5 June, Reynard asked his sergeant for leave to go outside of the camp to gather greens, which was granted. He took a haversack with him, and after about an hour returned to camp with the haversack full of dock greens and other wild greens. At noon he fell in for a formation.

Later that day or the next day, a local inhabitant named Mary Baker claimed that some soldiers had come to her house about two miles from the camp at around 11 in the morning of 5 June. She had an inventory of things that they had plundered which included "shirts, and a quantity of wearing Apparel." She identified Reynard as one of the perpetrators, and claimed that he had also killed a pig of hers and made off with it.

Reynard was put on trial for this crime on 7 June. Mary Baker was the only witness supporting the charge. Reynard claimed that he was away from the camp with leave but had not gone far and had only gathered greens. His sergeant and another grenadier both testified in his support, corroborating his story. Both testified that they were in the same mess as Reynard, that is, they prepared their food and dined together; this explained their explicit interest in having seen the greens that Reynard gathered, and both said that Reynard had nothing else with him when he returned to camp. As an aside, typically a mess consisted of 5 men; military authors of the era recommended that sergeants and soldiers mess separately, so the testimony in this trial indicates either that this company of the 37th did not heed these recommendations or that the size and composition of messes varied while the army was on campaign.

In a striking verdict, which is perhaps yet another mystery about Reynard, the military court found him guilty of the crime. Apparently they gave greater significance to the testimony of the injured party than to Reynard and his two comrades. There is no mention in the trial proceedings of how Mary Barker singled out Reynard, but there are other accounts of soldiers being paraded so that wronged inhabitants could recognize an offender in the ranks. It is possible that the officers who sat on the court were privy to information that was not explicitly presented at the trial. It also may be that the court wanted to set an example to stave off plundering by other soldiers.

Benjamin Reynard was sentenced to receive 1000 lashes. We have no information on the extent to which this punishment was inflicted. Sometimes soldiers who were severely punished, particularly on dubious evidence, deserted, but not this one. As described above, Reynard continued to serve through to the end of the war.

By Don N Hagist

Don is the owner of redcoat76.blogspot.com, a place for information about British soldiers who served during the American Revolution, 1775-1783. Take a look!