The second wave of states to leave the Union were the Upper South states. These included Virginia, North Carolina, Tennessee, Arkansas, and pro-confederate Kentucky and Missouri, who held divided loyalties. The Upper South states of Virginia, North Carolina, Tennessee, and Arkansas had a more extensive free population than the deep South and made up most of the Confederacy. Here, Jeb Smith looks at the causes for the seccession of these states.

This is part 2 in a series of extended articles form the author related to the US Civil War. Part 1 on Abraham Lincoln and White Supremacy is here.

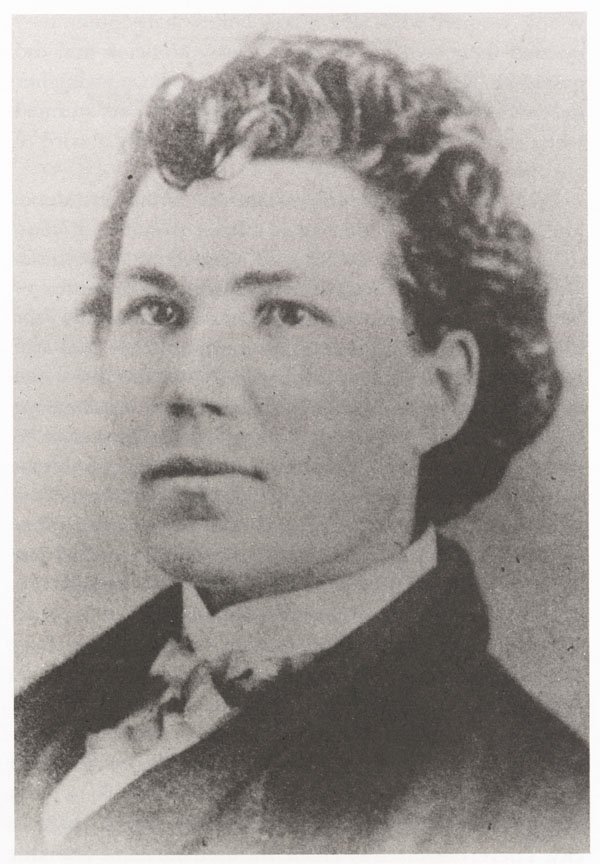

Henry Massey Rector, Governor of Arkansas at the time of secession.

"If centralism is ultimately to prevail; if our entire system of free Institutions as established by our common ancestors is to be subverted, and an Empire is to be established in their stead; if that is to be the last scene of the great tragic drama now being enacted: then, be assured, that we of the South will be acquitted, not only in our own consciences, but in the judgment of mankind, of all responsibility for so terrible a catastrophe, and from all guilt of so great a crime against humanity."

-Alexander Stephens

In general, there was a difference in the causes of secession between the original seven seceding "Cotton States" of the Deep South and the remaining Upper South.[1] When the Cotton States left the Union, the Upper South either turned down voting on withdrawal from the Union or voted against secession. Historian E. Merton Coulter writes, "The Majority sentiment in the Upper South had been unionist until Lincoln's call for troops...Upper South…had cried equally against coercion as secession."

When many historians talk about secession, they almost always ignore the Upper South; they unanimously point instead to the Cotton States. I believe this omission is because connecting slavery as a cause with the Upper South would be much more difficult. Further, looking at their causes of secession exposes the transformation of our Union into a centralized nation under Lincoln.

Lincoln's Call for Volunteers

"The South maintained with the depth of religious conviction that the Union formed under the Constitution was a Union of consent and not of force; that the original States were not the creatures but the creators of the Union; that these States had gained their independence, their freedom, and their sovereignty from the mother country, and had not surrendered these on entering the Union; that by the express terms of the Constitution all rights and powers not delegated were reserved to the States; and the South challenged the North to find one trace of authority in that Constitution for invading and coercing a sovereign State."

-Confederate General John B. Gordon Reminiscences of the Civil War New York Charles Scribner's Sons Atlanta The Martin & Hoyt Co.1904

Like the Cotton States, the Upper South saw itself as a collection of sovereign states joined by a contract, the Constitution; if that contract was violated or not upheld, it could and should be discarded. Many believed that peaceful secession would be allowed to occur and that the principles of the Declaration of Independence would be allowed to play out peacefully. DiLorenzo quotes the reactions of multiple northern newspapers as showing substantial support for secession. Many in the North perceived that this war was one of the self-governing states versus a controlling central federal government. In Lincoln Unmasked, DiLorenzo tells us that before being deported by Lincoln, northern politician Clement Vallandigham accurately describes Lincoln's purpose for war.

"Overthrow the present form of Federal-republican government, and to establish a strong centralized government in its stead...national banks, bankrupt laws, a vast and permanent public debt, high tariffs, heavy direct taxation, enormous expenditure, gigantic and stupendous peculation . . . No more state lines, no more state governments, but a consolidated monarchy or vast centralized military despotism."

-Clement L. Vallandigham D-Ohio

The North's support for secession was strong before it became clear how much of an impact secession would have on government funding, as the South was the North's "piggy bank." Further, free trade policies in the South would dominate the transatlantic trade since the North desired higher tariffs. If the South had been allowed to form their Confederacy, free trade policies in the South would have drawn even more commerce to Southern ports rather than Northern. So the North would lose the primary contributor to their economic plans, and they would lose out further due to their higher tax rates, and Europeans would trade with the free trade Confederacy. Not a good situation when you are looking to expand central spending.

Lincoln's call for volunteers to suppress the "rebellion" of the Cotton States caused the secession of the Upper South. The Cotton States felt that the federal government violated their agreement, and the Upper South believed that they had every right to leave, even if the Upper South disagreed with their reasons for leaving. As R. L. Dabney explained, "However wrongfully any State might resume its Independence without just cause, the only remedy was conciliation, and not force, that therefore the coercion of a sovereign State was unlawful, mischievous, and must be resisted. There Virginia took her stand."

According to many Republican politicians, the Union was not a voluntary contract between sovereign self-governing states governed by a constitution, but rather a centralized nation. Washington D.C., rather than "we the people," was the authority. The states, the people, were subjects, servants, and pupils of the state. In his first inaugural address, Lincoln said that the Union predated the Constitution. He referred to the Union as a "national government," and a "government proper," a "national union." Lincoln said, "The Union will endure forever, it being impossible to destroy it." He argued that the Union was not "an association of States in the nature of contract." His opinion was that "No State upon its own mere motion can lawfully get out of the Union."

The choice given to the Upper South was clear. They could either remain under the Republican-ruled coercive national government or join the Confederacy, whose Constitution maintained the Union and a compact of sovereign states. On June 4, 1861, The Western Democrat of Charlotte, North Carolina, said the Confederacy was "The only Republic now existing in America." The old Republic had become a democracy ruled by King Numbers. This was an easy choice for the Upper South.

The Upper South saw Lincoln's call for volunteers as a violation of the Constitution, a metamorphosis in government, and a violation of their states’ sovereignty. In 1863, the Address to Christians Throughout the World by the Clergy of the Confederate States of America suggested that the yankees, "Fight not to recover seceding states, but to subjugate them." This was a war of self-governing sovereign states versus a federal government that was willing to use military force against its own population to keep them under its jurisdiction. The Union was no longer a collection of self-governing bodies based on consent but a nation controlled by a dictatorial oligarchy. Consent of the governed was eliminated. The Upper South could not go along with what they viewed as oppressive actions by Lincoln and this transformation of the Republic.

"Subjection under an arbitrary and military authority, there being no law of Congress authorizing such calling of troops, and no constitutional right to use them....it is the fixed purpose of the government…to wage a cruel war against the seceding states...to reduce its inhabitants to absolute subjection and abject slavery...Lincoln...is now governing by military rule alone ...without any authority of law, having set aside all constitutional and legal restraints, and made all constitutional and legal rights dependent upon his mere pleasure...all his unconstitutional illegal and oppressive acts, all his wicked and diabolical purposes...in his present position of usurper and military dictator, he has been and is encouraged and supported by the great body of the people of the non slave holding States."

-Journal of the Convention of the People of North Carolina May 20, 1861, pp11-12

Professor of History at Longwood University Bevin Alexander wrote in his book, Such Troops as These, "Forced to choose between Lincoln's demand and what they believed to be morally correct and honorable, four Upper South states…seceded as well." The Upper South refused to become slaves to any government of unlimited power. In State Sovereignty and the Doctrine of Cohesion, J. K Spaulding wrote in 1860, "Hapless would be the condition of these states if their only alternative lay between submission to a self-construed government, or, in other words, unlimited powers and the certainty of coercion."

"Virginia...was not willing to secede hastily; but the demand of President Lincoln that she furnish troops to fight her sister States, ended all hesitation...preferring to fight in defence of liberty...to place themselves as barriers in the way of a fanatical Administration, and, if possible, stay the bloody effort to coerce independent states to remain in the Union."

-Address to Christians Throughout the World by the Clergy of the Confederate States of America Assembled at Richmond, VA April 1863

Preserving the Constitutional Republic

"All that the South has ever desired was that the Union, as established by our forefathers, should be preserved, and that the government as originally organized should be administered in purity and truth."

-Gen. Robert E. Lee quoted in The Enduring Relevance of Robert E Lee The Ideological Warfare Underpinning the American Civil War, Marshall DeRosa, Lexington Books 2014

"It is said slavery is all we are fighting for, and if we give it up we give up all. Even if this were true, which we deny, slavery is not all our enemies are fighting for. It is merely the pretense to establish sectional superiority and a more centralized form of government, and to deprive us of our rights and liberties."

-Confederate General Patrick Cleburne 1864

Lincoln and the Republican party had transformed the Union from a confederation of sovereign states to a centralized nation controlled by the majority. He endeavored to expand the central Government beyond its scope in order to achieve a political agenda. The North had abandoned the Constitution and the Republic and replaced them with a centralized democracy; in other words, a limitless government. The Upper South had no choice but to join the Confederate Constitution, which maintained the "original compact" theory of the Union.

It was believed in the South that it was the North that should secede. Quoting Henry Wise of Virginia, historian James McPherson says, "Logically the union belongs to those who have kept, not those who have broken, its covenants...the North should do the seceding for the South represented more truly the nation which the federal government had set up in 1789." The South saw the growing majority of the North interfering with the culture within their states and violating the Constitution. They observed that democracy and mob rule would take over America. The South wished to restore America to its original Constitution, a Republic of confederated states, in order to preserve liberty and self-government.

"If they [the North] prevail, the whole character of the Government will be changed, and instead of a federal republic, the common agent of sovereign and independent States, we shall have a central despotism, with the notion of States forever abolished, deriving its powers from the will, and shaping its policy according to the wishes, of a numerical majority of the people; we shall have, in other words, a supreme, irresponsible democracy. The Government does not now recognize itself as an ordinance of God...They have put their Constitution under their feet; they have annulled its most sacred provisions."

-Dr. James Henley Thornwell of South Carolina, Our Danger and our Duty Columbia, S. C.: Southern Guardian Steam-power Press, 1862

True unreconstructed Southerners carried no blind patriotism for a tyrannical democracy like "America." In a Democracy, not even the Constitution or the Declaration could protect people from the mob. Decades after the war, Major James Randolph wrote the popular southern folk song, "I'm a good old rebel." Here are some of the lyrics.

O I'm a good old rebel,

Now that's just what I am.

For this "fair land of freedom"

I do not care a damn...

I hates the Constitution,

This great republic too,...

I hates the Yankees nation

And everything they do,

I hates the Declaration,

Of Independence, too.

I hates the glorious Union-

'Tis dripping with our blood-

I hates their striped banner,

...

And I don't want no pardon

For what I was and am.

I won't be reconstructed,

And I don't care a damn

That was the old southerner. Propaganda like "land of the free," "home of the brave," meant nothing to a people who had their government toppled, their self-governance eradicated, their former ways of life destroyed.

State Secession Documents

With their actions and words, the states of the Upper South made it clear that Lincoln's call for volunteers, state sovereignty, and self-government were the primary causes of secession.

Arkansas

"If we go to the North we become instruments in the hands of Lincoln to coerce the seceding states. To this a large number of the people will never consent."

-The True Democrat Little Rock Arkansas March 15, 1861

Before Lincoln's call for volunteers, the people of Arkansas voted to stay in the Union by a vote of 23,626 to 17,927. On March 4, 1861, the Arkansas convention, led by a unionist president, voted to remain in the Union. However on March 12, 1861, The True Democrat Little Rock Arkansas warned "If Lincoln attempts to carry out the doctrines of his inauguration and to coerce the seceding states, that forces us at once to take our position by their side."

On May 6, 1861, after Lincoln's call for men, Arkansas officials gathered to revote. This time the result was 65-5 in favor of secession. In response to Lincoln's call for volunteers, Henry Rector, the Governor of Arkansas, said, "The people of this commonwealth are free men, not slaves, and will defend to the last extremity, their honor, lives, and property, against northern mendacity and usurpation." Arkansans' before and after votes and their declaration for secession demonstrate their motives for joining the Confederacy. The relevant section of the secession ordinance reads:

Whereas…Lincoln…has, in the face of resolutions passed by this convention, pledging the State of Arkansas to resist to the last extremity any attempt on the part of such power to coerce any State that had seceded from the old Union, proclaimed to the world that war should be waged against such States until they should be compelled to submit to their rule, and large forces to accomplish this have by this same power been called out, and are now being marshaled to carry out this inhuman design; and to longer submit to such rule, or remain in the old Union of the United States, would be disgraceful and ruinous to the State of Arkansas.

-Arkansas State Convention

Virginia

"Secession placed no State in so embarrassing a position as the great Commonwealth of

Virginia…There is no doubt that the great body of its citizens were opposed to the state’s seceding, but they were equally opposed to the coercion of the States which had already seceded."

-George Stillman Hillard Life and Campaigns of George B McClellan 1864 BiblioBazaar 2008

After the secession of South Carolina, Virginia stayed in the Union working to restore the seceding states back into the Union. However, on January 7, 1861, Virginia passed an anti-coercion resolution, by a vote of 112-5, describing the right of secession and state sovereignty. This declared that Virginia would oppose any attempt at coercion by the federal government. The resolution declares, "We will resist the same by all the means in our power." The state Governor declared, "I will regard an attempt to pass federal troops across the territory of Virginia, for the purpose of coercing a southern seceding state, as an act of invasion, which should be met and repelled." The general assembly "Resolved... that the basis of all just government is the "consent of the governed," and that such consent is the sanction of free, as force is the sanction of despotic, governments. That where this consent exists, there, whatever the form of the government, is liberty, and where it is wanting, there, whatever the form of the government, is tyranny." However, on April 4, 1861, Virginia voted to stay in the Union by a 2-1 margin.

Likewise, decades earlier, during the tariff controversy between South Carolina and the federal government the then Governor of Virginia said if any federal soldiers were to step on the soil of Virginia to coerce South Carolina to obey the federal tariffs they had nullified, it would happen only over his dead body. Such was the conviction of Virginian men against tyranny; it was no different in 1860. By calling for volunteers, Lincoln was ignoring Virginia's stance and resolve.

So when Lincoln called upon Virginia to supply troops to invade the Cotton States, Virginia's decision was predictable. Like most Virginians, Robert E Lee expressed his distaste for coercion when he wrote to his son George Washington Custis Lee in 1861, "A union that can be only maintained by swords and bayonets...has no charm for me." To Virginians, it was a clear distinction between government cohesion and liberty.

"As soon as it was known, that it was the intention of the northern president to usurp war-making powers, and wage war against sovereign states of the confederacy and that Virginia was called on to contribute men and money....no one doubted what her action would be...when the union became an engine for oppression...she could not hesitate to throw herself on the side of freedom."

-Richmond Whig Editorial April 19, 1861, Sic Semper Tyrannis State Independence Quoted in Virginia Iliad H.V Traywick, Jr Dementi Milestone Publishing INC 2016

Virginia voters gathered again after Lincoln's call for troops, and by a vote of 126,000 to 20,400, they left the Union. In his book, Reluctant Confederates, Daniel Crofts shows the great impact Lincoln's call for volunteers had on Virginians. Croft reports on the celebration of Virginians in Rockbridge County, who, after Fort Sumter, put up a confederate flag in celebration. In response, pro-unionist Virginians, who were by far the more numerous, erected a new, more enormous flagpole and put an American eagle on it. However, after Lincoln's call for volunteers, those same Unionists who had put the pole up with the American eagle threw it down. Rockbridge County, which had been majority unionist, then voted 1,728 to 1 for secession.

In the book, Three Months in the Southern States, Englishman Lt.-Colonel Arthur J. Fremantle wrote about a conversation he had with a Virginia woman who said that: "She had stuck fast to the Union until Lincoln's proclamation calling out 75,000 men to coerce the South, which converted her and such a number of others into strong Secessionists." Likewise, confederate artilleryman William Thomas Poague wrote, "Had Lincoln not made war upon the south, Virginia would not have left the union."

"Let us consider for a moment the results of a consolidated government, resting on force, as proposed by the dominant party at the north....a consolidated despotism, upheld by the sword and cemented by fear....now it [the union] has been seized upon by a sectional party, it is claimed that its powers are omnipotent, its will absolute, and it must and will maintain its supremacy, in spite of states and people, at the point of the sword."

-Richmond Whig Editorial A Government of Force April 10 1861 Quoted in Virginia Iliad H.V Traywick, Jr Dementi Milestone Publishing INC

Moreover, Governor John Letcher, (who wanted Virginia to abolish slavery) opposed secession before Lincoln's call for volunteers. After Lincoln's call, however, he became a firm secessionist.

"The President of the United States, in plain violation of the Constitution, issued a proclamation calling for a force of seventy-five thousand men, to cause the laws of the United states to be duly executed over a people who are no longer a part of the Union, and in said proclamation threatens to exert this unusual force to compel obedience to his mandates; and whereas, the General Assembly of Virginia, by a majority approaching to entire unanimity, declared at its last session that the State of Virginia would consider such an exertion of force as a virtual declaration of war, to be resisted by all the power at the command of Virginia."

-John Letcher Governor of Virginia

Virginia did not give a lengthy declaration of why it left the Union, just a short ordinance of secession and a mention of Lincoln's call for men.

The people of Virginia, in their ratification of the Constitution of the United States of America…declared that the powers granted under the said Constitution were derived from the people of the United States, and might be resumed whensoever the same should be perverted to their injury and oppression; and the Federal Government, having perverted said powers, not only to the injury of the people of Virginia but to the oppression of the Southern slaveholding States."

It was not northern coercion alone that Virginia objected to. When South Carolina and Mississippi were considering passing laws that would negatively affect Virginia financially unless they joined the Confederacy, Governor Letcher said, "I will resist the coercion of Virginia into the adoption of a line of policy, whenever the attempt is made by northern or southern states."

Tennessee

On February 9, Tennessee voters turned down secession by a 4-1 margin. However, things transformed radically after Lincoln's call for volunteers. Governor Isham Harris wrote President Lincoln saying that if the Federal Government would "coerce" the seceded states into returning, Tennessee had no choice but to join its Southern neighbors. He wrote "Tennessee will not furnish a single man for purposes of coercion, but 50,000 if necessary for the defense of our rights, and those of our southern brothers."

Harper’s Weekly quotes the Nashville Dispatch on April 13, saying, "An enthusiastic public meeting was held here tonight. Resolutions were unanimously adopted, condemning the Administration for the present state of affairs, and sympathizing with the South." Harper’s Weekly also quoted a Memphis paper saying, "There are no Union men now here." On May 9, in an address to the people of Tennessee, Governor Harris said, "Force, when attempted, changes the whole character of the Government; making it a military despotism, and those that submit become the abject slaves of power. The people of Tennessee have fully understood this important fact, and hence their anxiety to stay the hand of coercion. They well know that the subjugation of the seceded States involved their own destruction."

Harris and the people of Tennessee realized that cooperating in the subjugation of the Cotton States meant accepting their own future subjugation. Governor Harris recalled the Tennessee legislature on May 6 for another vote; voters would then approve secession on June 8 by a 2-1 margin. Reconciliation with a coercive government was out of the question; the Union was no longer. The founder's republic had vanished.

"If ever thus restored, it must, by the very act, cease to be a Union of free and independent States, such as our fathers established. It will become a consolidated centralized Government, without liberty or equality, in which some will reign and others serve the few tyrannize and the many suffer. It would be the greatest folly to hope for the reconstruction of a peaceful Union…The Federal Union of the States, thus practically dissolved, can never be restored."

-Isham G Harris, Senate Journal of the Second Extra Session of the Thirty-Third General Assembly of the State of Tennessee, which Convened at Nashville on Thursday, the 25th day of April, A.D 1861 Nashville J.O Griffith and Company, Public Printers 1861

North Carolina

"I have to say in reply that I regard the levy of troops made by the Administration for the purpose of subjugating the States of the South, as in violation of the Constitution and a usurpation of power. I can be no party to this wicked violation of the laws of the country, and to this war upon the liberties of a free people. You can get no troops from North Carolina."

-John Ellis, Governor of North Carolina Raleigh April 15, 1861, quoted in Harper's Weekly April 27, 1861

Before Lincoln's call to invade the Cotton States, support for the Union was overwhelming in North Carolina; they did not even vote on secession. However, after Lincoln's call for war, they unanimously adopted a secession ordinance. The same issue of Harper's Weekly quoted a dispatch from Wilmington North Carolina; "The Proclamation is received with perfect contempt and indignation. The Union men openly denounce the Administration. The greatest possible unanimity prevails." The effects were felt across political lines. McPherson writes, "Even the previously unionist mountain counties, seemed to favor secession."

Governor Ellis' proclamation on April 17 clarified why North Carolina stood with the South; "Lincoln has made a call for 75,000 men to be employed for the invasion of the peaceful homes of the South, and for the violent subversion of the liberties of a free people…this high-handed act of tyrannical outrage is not only in violation of all constitutional law, in utter disregard of every sentiment of humanity and Christian civilization…but is a direct step towards the subjugation of the whole South, and the conversion of a free Republic, inherited from our fathers, into a military despotism."

Missouri

"Sir...Your requisition, in my judgment, is illegal, unconstitutional, and revolutionary in its objects, inhuman and diabolical, and can not be complied with. Not one man will, of the State of Missouri, furnish or carry on such an unholy crusade."

-Missouri Governor Claiborne Jackson Jefferson City April 17, 1861 Quote in Harper's Weekly April 27, 1861

Missouri was almost entirely pro-union. When confederates sent delegates to Missouri to convince the state to join the South, they were booed and jeered so loudly that none could hear them. On March 21, 1861, the Missouri convention voted 98-1 against secession, but they, like Kentucky, kept their neutrality.

However, many in the state became outraged that their state sovereignty had been violated during the "Camp Jackson Affair." Union commander Nathaniel Lyon arrested the Missouri State Brigade, whom he feared were planning to seize the arsenal in St. Louis, and federal soldiers killed dozens of citizens during ensuing riots. Since the federal government violated the state's neutral position, support for secession grew within the state. James McPherson wrote, "The events in St Louis pushed many conditional unionists into the ranks of secessionists." Lyon then pushed the Governor and state legislature out of Jefferson City, creating more anti-union sentiment. These events led to the end of neutrality, which resulted in both a pro-confederate and pro-union government within the state. On November 28, the Confederate Congress accepted Missouri as the 12th confederate state. Pro-confederate Missouri's reasons for secession centered around constitutional violations by the Lincoln administration.

Whereas the Government of the United States…has wantonly violated the compact originally made between said Government and the State of Missouri, by invading with hostile armies the soil of the State, attacking and making prisoners the militia while legally assembled under the State laws, forcibly occupying the State capitol, and attempting through the instrumentality of domestic traitors to usurp the State government, seizing and destroying private property, and murdering with fiendish malignity peaceable citizens, men, women, and children, together with other acts of atrocity, indicating a deep-settled hostility toward the people of Missouri and their institutions; and Whereas the present Administration of the Government of the United States has utterly ignored the Constitution, subverted the Government as constructed and intended by its makers, and established a despotic and arbitrary power instead thereof.

-Missouri Causes of Secession

Kentucky

By a 3 to 1 margin, Kentucky voted to remain neutral, but after Lincoln's call for volunteers, support for the South began to spread. The Kentucky Governor wrote, "President Lincoln, I will send not a man nor a dollar for the wicked purpose of subduing my sister southern states." On April 16, 1861 Governor B. Magoffin wrote to Simon Cameron, Secretary of War saying "Your dispatch is received. In answer, I say emphatically that Kentucky will furnish no troops for the wicked purpose of subduing her sister Southern States."

However, the state's neutrality stance was violated by southern troops. In reaction, Kentucky would officially support the Union. Yet a pro-confederate government was established on December 10, 1861, and was accepted into the Confederacy by President Jefferson Davis as the 13th Confederate state. This Confederate government gave its causes of secession centered on limited government, Northern violations of the Constitution, and states’ rights.

Whereas, the Federal Constitution, which created the Government of the United States, was declared by the framers thereof to be the supreme law of the land, and was intended to limit and did expressly limit the powers of said Government to certain general specified purposes, and did expressly reserve to the States and people all other powers whatever, and the President and Congress have treated this supreme law of the Union with contempt and usurped to themselves the power to interfere with the rights and liberties of the States and the people against the expressed provisions of the Constitution, and have thus substituted for the highest forms of national liberty and constitutional government a central despotism founded upon the ignorant prejudices of the masses of Northern society, and instead of giving protection with the Constitution to the people of fifteen States of this Union have turned loose upon them the unrestrained and raging passions of mobs and fanatics, and because we now seek to hold our liberties, our property, our homes, and our families under the protection of the reserved powers of the States, have blockaded our ports, invaded our soil, and waged war upon our people for the purpose of subjugating us to their will; and Whereas, our honor and our duty to posterity demand that we shall not relinquish our own liberty and shall not abandon the right of our descendants and the world to the inestimable blessings of constitutional government.: therefore, be it ordained, that we do hereby forever sever our connection with the Government of the United States.

-Declaration of Causes of Secession Kentucky

Slavery's Impact on the Secession of the Upper South

"It was necessary to put the South at a moral disadvantage by transforming the contest from a war waged against States fighting for their Independence into a war waged against States fighting for the maintenance and extension of slavery…and the world, it might be hoped, would see it a moral war, not a political; and the sympathy of nations would begin to run for the North, not for the South."

-Woodrow Wilson, "A History of The American People" HardPress Publishing 2013

Slavery's involvement as a cause for secession in the Upper South is overstated. The states of the Upper South had protection for their slave property whether they stayed in the Union or joined the Confederacy. When the Deep South states left the Union, more slave states remained in the Union than joined the Confederacy. Most Upper South state declarations did not even mention slavery; if they did, it was only in passing and usually associated with violations of state's rights or the Constitution. Instead, they heavily spoke on state's rights, state sovereignty, and Lincoln's call for volunteers as the reasons for secession. Those states had previously chosen to stay with the Union before Lincoln's call but could no longer remain under a government of force.

Slavery was Safer in the Union Than the Confederacy

"Seven-tenths of our people owned no slaves at all, and to say the least of it, felt no great and enduring enthusiasm for its preservation, especially when it seemed to them that it was in no danger.'"

-John G. Barrett, The Civil War in North Carolina U of North Carolina Press 1995

The Union would protect slavery better than a Confederacy. Slavery was constitutionally protected in both the northern and southern states for the entirety of the civil war. Moreover, Lincoln and the North supported the Corwin Amendment, which would permanently enshrine slavery in the U.S. Constitution. In his first inaugural address, Lincoln said this of the proposed amendment, "To the effect that the Federal Government shall never interfere with the domestic institutions of the States, including that of persons held to service...holding such a provision to now be implied constitutional law, I have no objection to its being made express and irrevocable."

"No amendment shall be made to the Constitution which will authorize or give Congress the power to abolish or interfere, within any State, with the domestic institutions thereof, including that of persons held to labor or service by the laws of said State."

-Corwin Amendment

The U.S. supreme court supported the fugitive slave laws, allowing federally funded agents to return runaway slaves to their masters. On the other hand, the Confederacy was unable to protect slaveowners when slaves fled to the North. In his inaugural address, Lincoln pointed this out, saying, "while fugitive slaves, now only partially surrendered, would not be surrendered at all by the other."

The 1860 Republican platform Plank 4 said that slavery was a state issue, and they would not interfere with it in states that already had slaves. In his inaugural address, Lincoln said, "I have no purpose, directly or indirectly, to interfere with the institution of slavery in the States where it exists. I believe I have no lawful right to do so, and I have no inclination to do so." Likewise, on May 26, 1861, General MClellan said, "Not only will we abstain from all such interference (with slaves), we will, on the contrary, with an iron hand crush any attempt at insurrection on their part." It is no wonder a leader of the Whig Party in Missouri said, "Howard County is true to the Union. Our slaveholders think it is the sure bulwark of our slave property."

Even after the deep South left the Union, the federal government decided it would not end slavery, in the House in February and the Senate on March 2, 1861. On July 22, 1861, Congress declared, "This war is not waged, nor (the) purpose of overthrowing… the rights or established institutions of those states." On October 8, 1861, the Washington D.C. newspaper, The National Intelligencer, said, "The existing war had no direct relation to slavery." On November 7, 1861, Commanding General McClellan said, "The issue for which we are fighting, that issue is the preservation of the Union... I express the feelings and opinions of the president when I say that we are fighting only to preserve the integrity of the Union." On August 15, 1864, long after the Emancipation Proclamation, Lincoln said, "So long as I am President. It shall be carried on for the sole purpose of restoring the Union."

This is not to say that no one in the Upper South was upset over the Republican's intrusion into the states' rights on this issue in the western territories. There was a minor secession movement within the Upper South on the issue of slavery, especially in Virginia and Arkansas, but they were a minority. In fact, after Lincoln's call for troops, many slave owners in the Upper South argued to stay in the Union since Lincoln was powerless to interfere with slavery.

"Is there any good reason why we should change our position? I believe that so far as the North is concerned, the prospect for the full recognition of Southern rights is better than it was at the time of Lincoln's election, or at any time within several years before. The Governors of several Northern States, including the great States of New York and Pennsylvania, have recommended the faithful observance of all the laws intended for the protection of slave property, and the repeal of all the personal liberty bills... Lincoln's administration is powerless to harm us. Before its close, his party will be scattered into fragments."

-Rep. Thomas N. Crumpler of Ashe County N.C to the House of Commons on January 10, 1861

Jeb Smith is the author of Missing Monarchy: What Americans Get Wrong About Monarchy, Democracy, Feudalism, And Liberty (Amazon US | Amazon UK) and Defending Dixie's Land: What Every American Should Know About The South And The Civil War (written under the name Isaac. C. Bishop) - Amazon US | Amazon UK

You can contact Jeb at jackson18611096@gmail.com

[1] This article was taken with permission from a section of Defending Dixie’s Land: What Every American Should Know About The South And The Civil War.