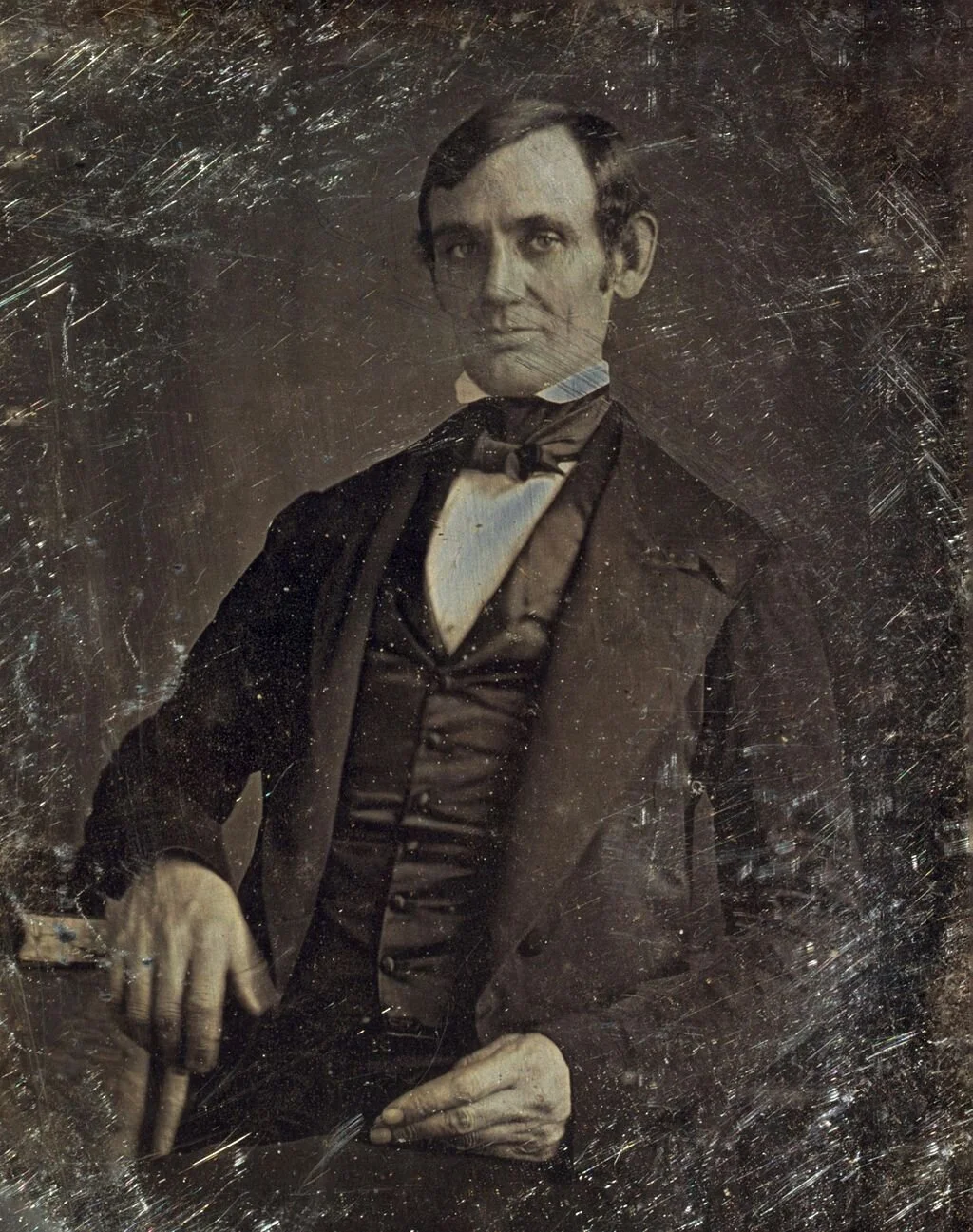

Widely considered the greatest President in American history, much has been written about the man, the myth, the legend: Abraham Lincoln. From his acclaimed debates with Stephen A. Douglas, to his creation of the Emancipation Proclamation, to the Gettysburg Address, and finally his tragic death by the hands of John Wilkes Booth after the Civil War, President Lincoln will forever be an icon of US history. Even Lincoln’s childhood and early adulthood has come under scholarly examination. However, what is less spoken of is the strange but prolific wrestling career of the Great Emancipator. Brenden Woldman explains.

A painting of Abraham Lincoln reading as a boy. By Eastman Johnson, 1868.

In the moderately sized city of Stillwater in Payne County, Oklahoma stands the National Wrestling Hall of Fame. Enshrined within those hallowed halls are America’s greatest wrestlers, from collegiate athletes to Olympic champions. But there is one man who was granted a spot within the Hall for his grappling tactics within the ring, and earned him an “Outstanding American” honor.[1] Though his gangly stature became a point of insult for his political rivals and contemporaries, with one man once telling Lincoln that he did not possess the “features the ladies would call handsome,” the future president as a young man was, surprisingly, built from stone.[2] Lincoln may have been a thin, wiry young man standing at 6 feet, 4 inches and 180 lbs., but years of working manual labor as both a farmer in the Kentucky backwoods as well as a rail splitter helped forge a naturally strong specimen of a man who towered over any and all who stood beside him.[3]

Wrestling fame

Though he had no dreams of sporting grandeur, the future president, like many of his contemporaries who worked manual labor jobs, enjoyed physical activities like wrestling as a leisure activity. But just like in his political career Lincoln was a calculated and ambitious wrestler. Still, conversely to his political persona the young Lincoln was a confident sportsman who could be simply described as cocky. Lincoln’s confidence in his ability stemmed from his mastery of the “catch-as-catch-can” manner of wrestling, a brawling and combative style known for its bull-like aggressive rushes and hand-to-hand combat tactics to the opponent. Nevertheless, this bar fight style of wrestling still needed more than a hint of skill to pin a rival.[4] Lincoln’s rare mix of thin and wiry but broad, strong, and smart athlete made him nearly impossible to beat. His physical prowess made Bill Green, a local store owner from New Salem, Illinois, note that “[Lincoln] can outrun, outlift, outwrestle and throw day any man in Sangamon County,” after the young man beat multiple opponents in one day.[5] Moreover, Lincoln matched his reputation as an in-ring force with his loud public trash talking. After decisively defeating another opponent with a single toss in the ring, Honest Abe being as honest as he could be looked into an entire crowd and challenged any and all who dared to face him. Lincoln shouted, “I’m the big buck of this lick. If any of you want to try it, come on and whet your horns.”[6]Unsurprisingly, there were no takers.

The legend of Lincoln the wrestler continued to grow during the late 1820s and into the early 1830s. But what made Lincoln a local wrestling legend came in 1831, when the Great Emancipator was only 22 years old. Lincoln was quietly tending to the store he worked at as a clerk in New Salem when his boss Denton Offutt out of the blue challenged any of the local Clary’s Grove Boys to a good natured wrestling match with his star clerk.[7] The Clary’s Grove Boys, who were known for their rowdy, fraternity-like attitude toward frontiers life, enjoyed drinking and fighting more than anyone around.[8] After Offutt boasted that no one could beat his employee, the Clary’s Grove Boys’ “champion wrestler” Jack Armstrong took the challenge, believing, that he “had found only another subject by which [they] could display its strength and prowess.”[9] Lincoln accepted the challenge, getting up from behind his counter, and prepared to wrestle the feared Armstrong.

Confident that he could outmatch the taller but gawky Lincoln, Armstrong felt no fear. Who could blame him? Lincoln had been, and would continue to be, judged by his physical appearance his entire life. However, soon after the match began, the Clary’s Grove Boys champion realized he had bit off more than he could chew. Lincoln from the start was able to control the match due to his enormous reach, forcing Armstrong to fight dirty as a means of desperation.[10] Annoyed by the lack of sportsmanship, Lincoln lost his temper and, according to legend, won the match by grabbing Armstrong by the neck, raising him above his head, shaking him around, and slamming him on the ground.[11] The crowd was shocked by Lincoln’s clear victory, and the rest of the Clary’s Grove Boys were angered by the result. Enraged, the Clary’s Grove Boys began to threaten Lincoln. Luckily, Armstrong bounced back up and defended the future president. Smiling, Armstrong looked at his friends and said, “Boys, Abe Lincoln is the best fellow that ever broke into this settlement. He shall be one of us.”[12]

A very impressive career

Lincoln gained the respect of Jack Armstrong and the rest of the Clary’s Grove Boys. As a result of his victory, the young Lincoln gained the reputation as the champion wrestler of New Salem, gladly taking on, and easily defeating, any and all opponents who came to challenge him. Amazingly, Lincoln was nearly impossible to beat. According to historians who have researched the win/loss record of Honest Abe, Lincoln has only one confirmed lose in allegedly more then 300 matches over the course of 12 years.[13] That sole lose came at the hands of Pvt. Lorenzo Dow Thompson, the St. Clair wrestling champion whom Lincoln met when he was a Captain during the Black Hawk War. Upon hearing of Thompson’s prowess at wrestling, Lincoln was certain in his own ability and “told my boys I could throw [Thompson].”[14] As confident as ever, Lincoln set up a match between himself and the private when both of their regiments had down time from fighting. Unfortunately, much like how Armstrong underestimated Lincoln, Lincoln underestimated Thompson. Though still in his physical prime, Lincoln realized rather quickly after the match began that he was wrestling “a powerful man” in Thompson, and that “the struggle [of winning] was a sever one.”[15] Shockingly, Lincoln for the first time in his career was thrown out of the ring and lost the match. When his men came to the defense of their captain claiming Thompson had cheated, Lincoln laughed and said Thompson won fairly. When asked how did he know, Lincoln simply said, “Why, gentlemen, that man could throw a grizzly bear.”[16]

In retrospect

There is something funny when we read or write about famous historical figures like Abraham Lincoln. For the most part, we think we know everything there is to know about a figure because we have been indoctrinated about the “greatest hits” of these figures. We all know about the stoic Lincoln who unified the Union during the Civil War, freed the slaves, and was assassinated, but we should never think we know everything about someone. Moreover, the importance of Lincoln as a wrestler transcends something more than an interesting tidbit of information about America’s greatest president. Lincoln learned about his own strength and confidence as well as humility through the sport. Writer and historian David Fleming said it best, noting that “when his wrestling skill diminished, Lincoln’s leadership qualities emerged.”[17] Without what he learned from wrestling, Abraham Lincoln would not have been the same man that became America’s sixteenth President.

Do you think Abraham Lincoln’s wresting career was important for his later political career? Let us know below.

You can read Brenden’s previous article on US politics: Violence in the Senate – Slavery, Honor and the Caning of Charles Sumner here.

[1] Christopher Klein, “10 Things You May Not Know About Abraham Lincoln,” History.com (A&E Television Networks, November 16, 2012), https://www.history.com/news/10-things-you-may-not-know-about-abraham-lincoln)

[2] Susan Bell, “Lincoln's Looks Never Hindered His Approach to Life or Politics,” USC News (USC, February 19, 2015), https://news.usc.edu/75846/lincolns-looks-never-hindered-his-approach-to-life-or-politics/)

[3] “The Railsplitter: Abraham Lincoln: An Extraordinary Life,” National Museum of American History (National Museum of American History, n.d.), https://americanhistory.si.edu/lincoln/railsplitter)

[4] Bob Dellinger, “Wrestling in the USA,” National Wrestling Hall of Fame (National Wrestling Hall of Fame, n.d.), https://nwhof.org/stillwater/resources-library/history/wrestling-in-the-usa/)

[5] David Fleming, “The Civil Warrior,” Sports Illustrated (Sports Illustrated, n.d.), https://vault.si.com/vault/1995/02/06/the-civil-warrior-on-the-us-frontier-young-abe-lincoln-was-a-great-wrestler-and-sportsman)

[6] Klein, “10 Things You May Not Know About Abraham Lincoln,” https://www.history.com/news/10-things-you-may-not-know-about-abraham-lincoln

[7] Dellinger, “Wrestling in the USA,” https://nwhof.org/stillwater/resources-library/history/wrestling-in-the-usa/, R.J. Norton, “Abraham Lincoln's Wrestling Match,” Abraham Lincoln Research Site (Abraham Lincoln Research Site, n.d.), https://rogerjnorton.com/Lincoln48.html)

[8] Norton, “Abraham Lincoln’s Wrestling Match,” https://rogerjnorton.com/Lincoln48.html

[9] Dan Evon, “Is Abraham Lincoln in the Wrestling Hall of Fame?,” Snopes.com (Snopes.com, n.d.), https://www.snopes.com/fact-check/lincoln-wrestling-hall-of-fame/

[10] Dellinger, “Wrestling in the USA,” https://nwhof.org/stillwater/resources-library/history/wrestling-in-the-usa/

[11] Dellinger, “Wrestling in the USA,” https://nwhof.org/stillwater/resources-library/history/wrestling-in-the-usa/, Norton, “Abraham Lincoln’s Wrestling Match,” https://rogerjnorton.com/Lincoln48.html

[12] Norton, “Abraham Lincoln’s Wrestling Match,” https://rogerjnorton.com/Lincoln48.html

[13] Bryan Armen Graham, “Abraham Lincoln Was A Skilled Wrestler And World-Class Trash Talker,” Sports Illustrated (Sports Illustrated, February 12, 2013), https://www.si.com/extra-mustard/2013/02/12/abraham-lincoln-was-a-skilled-wrestler-and-world-class-trash-talker)

[14] Evon, “Is Abraham Lincoln in the Wrestling Hall of Fame?,”https://www.snopes.com/fact-check/lincoln-wrestling-hall-of-fame/

[15] Ibid.,

[16] Ibid.,

[17] Graham, “Abraham Lincoln Was A Skilled Wrestler and World-Class Trash Talker,” https://www.si.com/extra-mustard/2013/02/12/abraham-lincoln-was-a-skilled-wrestler-and-world-class-trash-talker