The Suez Crisis of 1956 was a watershed moment in the history of the post-colonial world. The effects of the ill-fated military plan devised in secret between the forces of the United Kingdom, France and Israel, to invade and retake the Suez Canal following an invasion by Egyptian forces, would be felt much further than merely on Egyptian soil. Indeed, it is often cited as the event which ended European - and more accurately British - hegemony in international relations. From the Suez Crisis onwards, the United States would almost invariably take the lead in conducting large-scale military operations across the world.

However, the effect that the Crisis had within Egypt itself is less well documented. Here, Conor Keegan gives a brief explanation of the measures taken by Nasser immediately post-1956 to remove the mutamassirun community, with a specific focus on the effects of these policies on the Jewish population of Egypt.

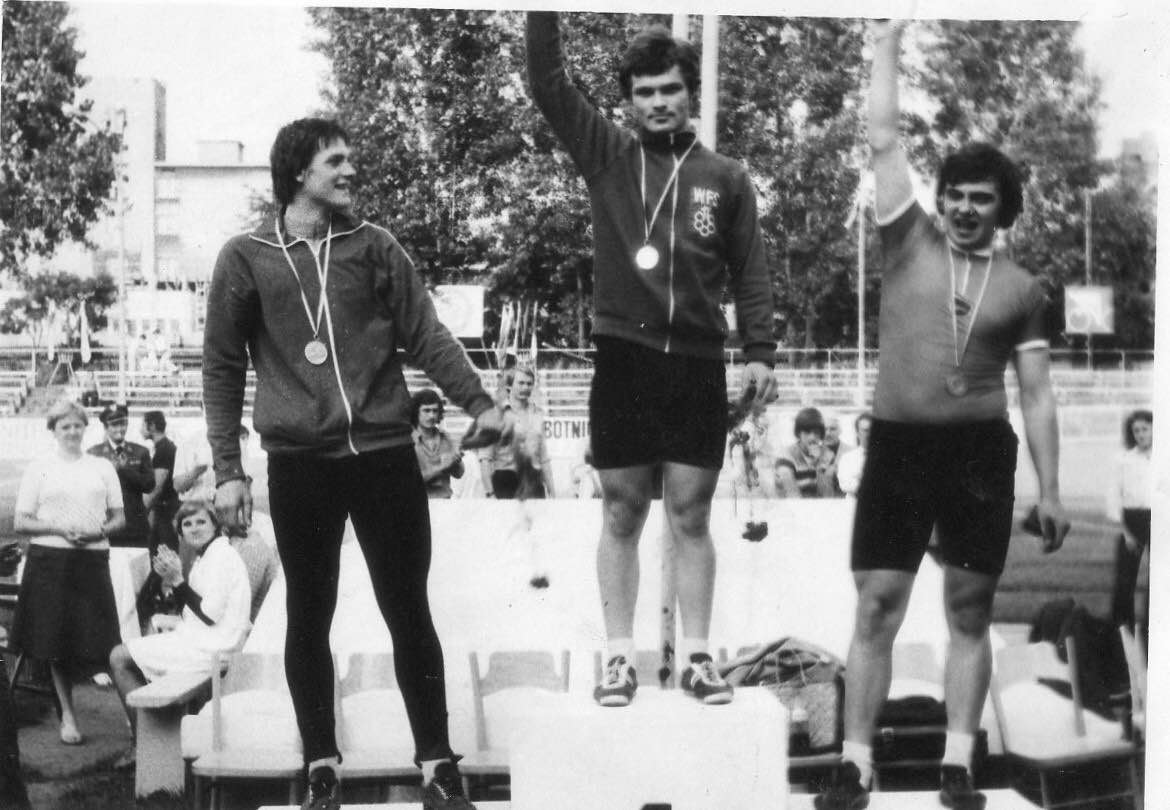

General Nasser (center of picture with hand in the air), Alexandria, Egypt, 1954.

The Mutamassirun

The Suez Crisis, aside from producing an understandable rise in support for President Gamal Abdel Nasser and his regime, had devastating effects for persons living within Egypt who had become ‘egyptianized’ i.e. those who were not Egyptian citizens; or those whose ancestry was not wholly Egyptian, but had attained Egyptian citizenship through various legal statutes.

These people were collectively known as the mutamassirun, and, in the immediate post-colonial period in Egypt (from 1922 onwards) they owned a large share of capital and operated a large number of businesses in Egypt. They were also acknowledged to have made significant contributions to Egyptian cultural, religious and linguistic diversity in the past. Although measures to expel members of the mutamassirun were already underway before the Suez Crisis came to a head, the Crisis is widely seen as giving Nasser the necessary impetus and legitimacy to proceed to make it extremely difficult for ‘egyptianized’ persons to remain in Egypt.

It was a natural step for Nasser to seek to blame the Suez Crisis on the mutamassirun population. After all, Nasser had risen to power on an avowedly pan-Arab, anti-colonial message. As Britain had directly ruled Egypt from the late nineteenth century until 1922, and France had previously invaded under Napoleon in 1798, the mutamassirun were easy targets for blame post-Crisis Egypt, as many were of British or French nationality or extraction. There was also a sizeable population of Jews living in Egypt around the turn of the twentieth century. As the pre-Crisis period coincided with an increasingly confident and assertive Zionist movement, leading up to the creation of Israel in 1948, which led to great discomfort across Arab states, the Crisis only provided Nasser with a further reason to expel large numbers of the Egyptian Jewish population in its aftermath.

Impact on the Jewish Population

For the Jews specifically (including those Jews who also happened to be British or French citizens), Nasser’s policy of removal post-1956 was carried out in two ways: expulsion and ‘voluntary’ emigration. With regard to expulsion, the Egyptian government was able to make the number of Jews removed from Egypt seem much lower than the actual number by statistical sleight of hand: the estimate that at least 500 Egyptian and stateless Jews were expelled from Egypt by November 1956 does not include the expulsion of those Jews that were French or British citizens, nor does it include any member of a family who was not deemed by the Egyptian authorities to have been the ‘head of a family’, but who nonetheless had to leave Egypt along with the head of their family.

Furthermore, the Egyptian authorities used more informal (and ‘voluntary’) methods to expel Jews, which proved to be effective. These measures included widespread intimidation, economic coercion and ‘voluntary’ declarations made by those Jews who were Egyptian citizens renouncing their citizenship. When these methods are included, it is estimated that by the end of June 1957 between 23,000 and 25,000 of Egypt’s 45,000 Jews had left the country.

Making Citizenship Harder to Obtain

In additional to expulsions, the Egyptian government also actively set about depriving the mutamassirun in general of citizenship in the aftermath of the Crisis. In November 1956, Egyptian citizenship law was amended so that only persons who were resident on the territory of Egypt on January 1, 1900, and who had maintained their residence in Egypt from that date to the coming into force of the amendment on November 22, 1956, were entitled to Egyptian citizenship. Therefore, by virtue of this provision, it was a relatively uncomplicated task for the Egyptian government to retroactively deprive the mutamassirun in general of Egyptian citizenship. This policy was only made easier for the Egyptian government to enforce due to the fact that most mutamassirun did not possess official papers of any kind which proved their continuous residence in Egypt between the relevant dates.

The amended law was even clearer when it came to providing for Jewish citizens of Egypt: the amendment clearly provides that citizenship should not be given to ‘Zionists’. Therefore, while the attempt to make uncertain the position of the general mutamassirun population after 1956 was arguably camouflaged by somewhat confusing references to continuous residence in Egypt between two specific dates, the provisions of the legislation left no room for doubt that the Jewish population was prioritized by Nasser’s government when it came to identifying groups from whom they would seek to withdraw rights and privileges.

Therefore, it can be seen that President Nasser and his government used various legal, procedural, formal and informal measures to effectively expel and exclude the mutamassirun from Egyptian society, territory and nationality. While measures excluding this much-maligned group were not unusual in the broad expanse of Egyptian history, the measures enacted after the Suez Crisis of 1956 were more intense and more in the vein of ostracization (as opposed to discrimination) than any previous measures. Therefore, even though the Suez Crisis had far-reaching and important effects across the world, the Crisis also had drastic consequences for ‘egyptianized’ foreigners in Egypt, and most acutely affected the Jewish population.

What do you think of this article? Let us know your thoughts below…

Sources

Gorman, Anthony, Historians, State and Politics in Twentieth Century Egypt: Contesting the Nation 2003 Routledge Curzon

Harper, Paul, The Suez Crisis 1986 Wayland

Kazamias, Alexander, ‘The Purge of the Greeks from Nasserite Egypt’ 2009 Journal of the Hellenic Diaspora 35(2) 13-34

Laskier, Michael M, ‘Egyptian Jewry under the Nasser Regime 1956-70’ 1995 Middle Eastern Studies 31(3) 573-619