James K. Polk, eleventh US President, has gone down in history as the man who finished the westward expansion of America through a great plan to acquire California and Oregon. And even more remarkably, he achieved this very rapidly.

But, did he really have a grand strategy to expand America and achieve a number of great measures? Or did events just play their course? William Bodkin returns to the site and explains the legend of James K. Polk.

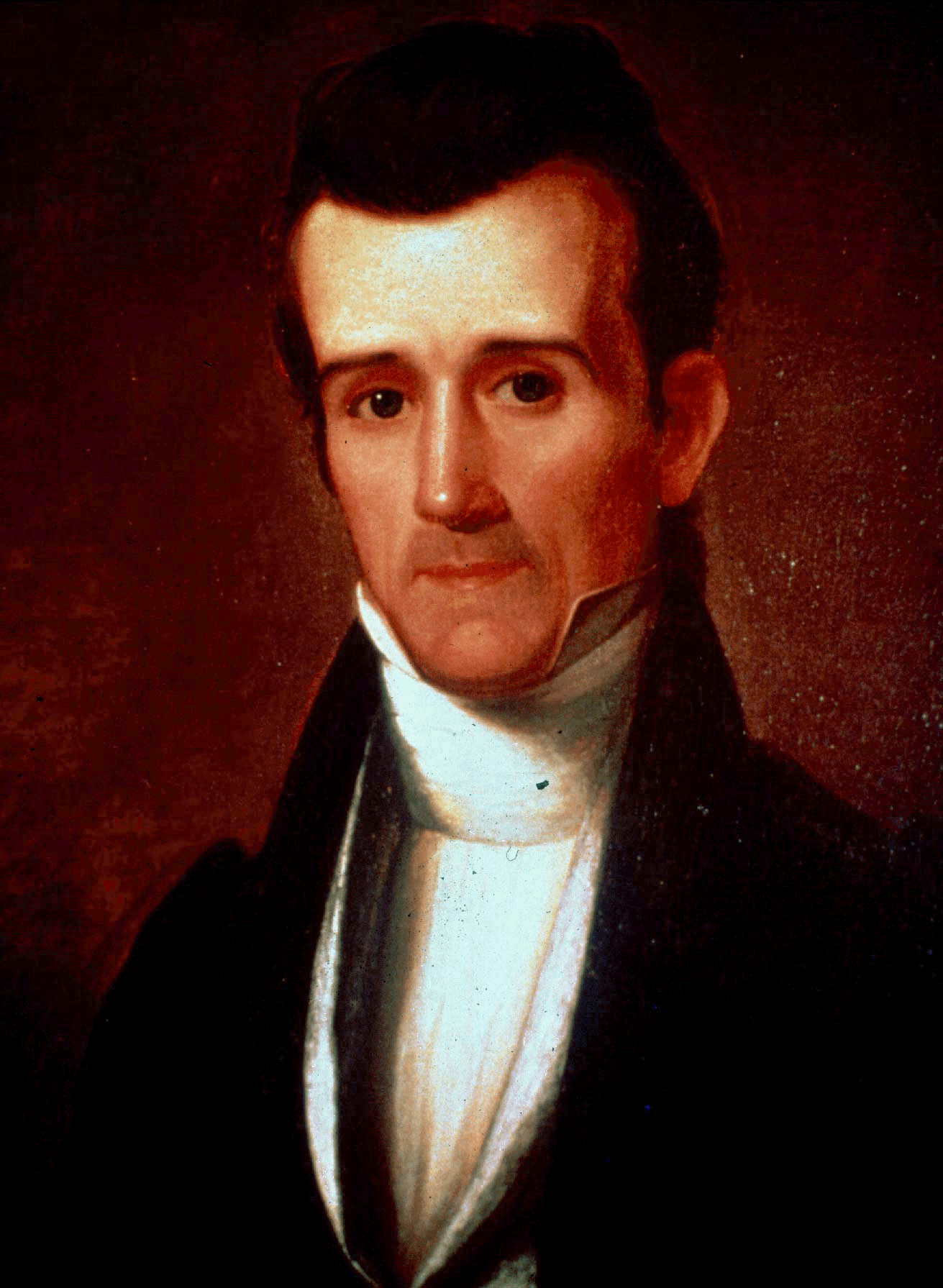

A portrait of James K. Polk.

What if the one thing America remembered about a President was false? James K. Polk, who seemingly came from nowhere to become America’s eleventh President, is remembered for the four “great measures” of his Administration: (1) obtaining California and its neighboring territories following the Mexican War; (2) negotiating the purchase of the Oregon territories from Great Britain; (3) lowering the nation’s tariff on imported goods to promote free trade; and (4) establishing an independent treasury to put an end to the nation’s money problems. Polk is celebrated for stating, at the outset of his Administration, that he would accomplish these goals in four short years.

Polk’s bold prediction and follow through led another President, Harry Truman, to describe him as the ideal Chief Executive. Truman famously opined that Polk knew what he wanted to do, did it, and then left. Unfortunately, while these are unquestionably Polk’s accomplishments, there is little to no evidence that he predicted them. Instead, the prediction seems to have been created after the fact by one of Polk’s top advisors, historian George Bancroft.

The President From Nowhere

How did Polk become President? In 1844, John Tyler was winding down William Henry Harrison’s term of office. Tyler, in becoming President on Harrison’s death, alienated the two dominant political parties in America, the Democrats and the Whigs. Tyler had angered the Democrats prior to becoming President, when, although a Democrat, he agreed to run with Harrison on the Whig ticket. When he became President, Tyler governed mostly as a Democrat, angering the Whigs.

Waiting in the wings for the Democrats was Martin Van Buren, yearning to avenge his loss to Harrison. Van Buren, however, before even receiving the nomination, stumbled on one of the key issues of the day, admitting Texas to the Union. Texas had declared its independence from Mexico in 1836, seeking to join the United States. Tyler, in one of the last acts of his Presidency, pushed to admit Texas, but failed.

The presumed Presidential nominees, though, both opposed admitting Texas. Henry Clay, for the Whigs, opposed Texas because it would be admitted as a slave state. Van Buren, in a political calculation that backfired, claimed he opposed admitting Texas because he didn’t want to insult Mexico. In truth, Van Buren believed that supporting Texas’s admission into the Union would cost him his traditional, staunchly abolitionist Northeast electoral base. The gamble failed. It cost Van Buren the support of the political powerhouse who had actually propelled him to the Presidency: Andrew Jackson.

Jackson favored admitting Texas. Furious over Van Buren’s position, Jackson summoned Polk, his Tennessee protégé, to The Hermitage. Polk, still reeling from a run of bad political luck, had been eyeing the Vice-Presidency. A former Congressman, he had been Speaker of the House of Representatives from 1835-39, largely through Jackson’s support. He left the Speaker’s chair to become Governor of Tennessee, but served only one term before being ousted in 1841. In 1843, Polk tried and failed to win back the governor’s mansion.

At his estate, Jackson made his views plain. Van Buren’s Texas position must be fatal to him. The nominee would be an “annexation man,” preferably from what was then the American Southwest, meaning, Tennessee. Polk was the best candidate. As usual, Jackson got want he wanted. At the Democrats’ Baltimore convention, Van Buren’s support eroded and the Democrats turned to Polk who narrowly won election over Clay.

‘Thigh-Slapping” Predictions

Polk, once in office, resolved that despite Jackson’s support, he would himself be President of the United States. According to Polk’s Secretary of the Navy and Ambassador to Great Britain, historian George Bancroft, Polk set his goals early on. Bancroft said that in a meeting with Polk during the early days of the Administration, the President “raised his hand high in the air,” brought it down “with great force on his thigh,” and declared the “four great measures” of his administration. First, with Texas on the road to statehood, the question of Oregon would be settled with Great Britain. Second, with Oregon and Texas secure, California and its adjacent areas would round out the continent. Third, the tariff, which was crippling the Southern states economically, would be made less protective and more revenue based. Fourth, an independent national Treasury, immune from the banking schemes of recent years, would be established.

Bancroft’s tale is problematic in two respects. First, such a display was uncharacteristic of Polk. Polk has been described as peculiarly simple. He was a straightforward man and not particularly outspoken. Polk was a workaholic, with few friendships other than his wife, no children, and no interests other than politics. By most accounts, he was phlegmatic in disposition at best, and unlikely to engage in any dramatic exclamation.

The second problem with this story is that it comes from Bancroft. While a superb historian, Bancroft is unfortunately a dubious source. He served in Polk’s administration, wholeheartedly endorsed its expansionist policies, and burned to write Polk’s official biography. Polk rejected Bancroft as administration historian, instead seeking to have his former Secretary of War, William Marcy, do the job. Marcy had been in Washington for the entire administration; whereas Bancroft had left for London in 1846. Despite this, Bancroft remained loyal to Polk. By the late 1880s, Bancroft was the only remaining living member of Polk’s cabinet.

This is significant because during the 1880s, a number of historians dismissed Polk as being controlled by events round him and having been bullied into his expansionist policies. The young historian and future President Theodore Roosevelt took this view, finding Polk’s administration not to be particularly capable. Other historians viewed the Mexican War as having led to the Civil War, and condemned Polk for it.

Bancroft was offended by these assessments. By the late 1880s, despite Polk’s previous opposition, Bancroft resolved to write a biography of Polk. The earliest known mention of the “thigh-slapping” conversation is in an unpublished manuscript located in Bancroft’s papers titled “Biographical Sketch of James K. Polk,” apparently written in the late 1880s. Historian James Schouler, in his “History of the United States of America, Under the Constitution,” first published the story. Schouler noted that Bancroft had relayed the anecdote to him in a February 1887 letter. After its initial publication, the “thigh-slapping” story was re-published, gradually taking on a life of its own.

Recent scholarship, however, indicates that Bancroft might have manufactured the incident. On August 5, 1844, Bancroft wrote an admiring letter to Polk where he inventoried all of the administration’s accomplishments, including the annexation of Texas, the post-war purchase of New Mexico and California, the establishment of the Treasury and the overthrow of the protective tariff. Bancroft wrote to Polk that these accomplishments “formed a series of measures, the like of which can hardly ever be crowded into one administration of four years & which in the eyes of posterity will single yours out among the administrations of the century.”

Did Bancroft help the “eyes of posterity” look more favorably toward James K. Polk? It seems likely. However, an historian, when examining primary sources, can never truly know the intent of historical actors and what motivated their writings. Despite seeming evidence to the contrary, the ”thigh-slapping” story could have happened as Bancroft said it did. History, it has been said, is written by the victors. There are times though, when the person who writes the history determines the identity of the victor and the extent of the victory.

Did you enjoy this article? If so, tell the world! Tweet about it, like it, or share it by clicking on one of the buttons below…

Finally, William's previous pieces have been on George Washington (link here), John Adams (link here), Thomas Jefferson (link here), James Madison (link here), James Monroe (link here), John Quincy Adams (link here), Andrew Jackson (link here), Martin Van Buren (link here), William Henry Harrison (link here), and John Tyler (link here).

References

- Anthony Berger, “2014 Presidential Rankings, No. 7: James K. Polk,” www.deadpresidents.tumblr.com

- Walter R. Borneman, “Polk: The Man Who Transformed the Presidency and America,” Random House, 2008.

- Tom Chaffin, “Met His Every Goal? James K. Polk and the Legends of Manifest Destiny,” University of Tennessee Press, 2014.

- Milo Milton Quaife, editor, “Diary of James K. Polk during His Presidency, 1845-1849.” A.C. McClurg & Co., Chicago, 1910.

- Sean Wilentz, “The Rise of American Democracy: Jefferson to Lincoln,” WW Norton and Company, 2005.

- Jules Witcover, “Party of the People, A History of the Democrats,” Random House, 2003.